UPDATE: Check out our 2018 ranking of the most miserable sports cities!

The Chicago Cubs haven’t won a World Series since 1908 — the longest and most miserable championship drought in the big four professional sports leagues (NBA, NFL, NHL and MLB). But at least Chicago sports fans can turn with pride to the Blackhawks, winners of two Stanley Cups in the past five years, and the Bulls, winners of six NBA championships with Michael Jordan in the 1990s.

Not every city’s sports fans are quite as fortunate. In some proud cities, the misery of losing is a way of life: having a playoff-bound team is far from guaranteed, making a deep run in the post-season would be a rare gift from the gods, and the phrase “plan the parade” is just a cruel joke from a friend in Boston.

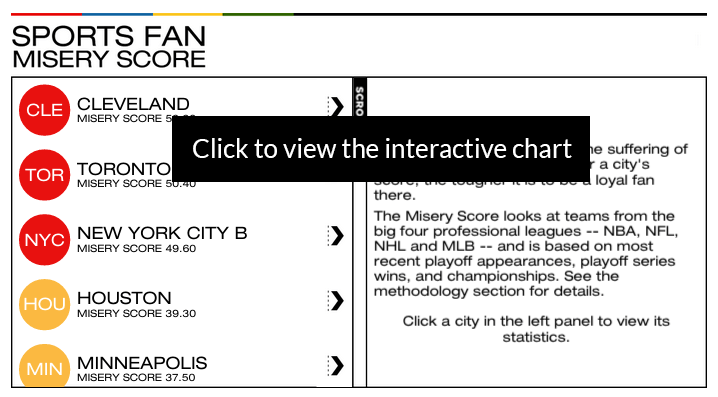

It ain’t easy being a long-suffering sports fan in cities like Toronto or Cleveland, Minneapolis or Washington, and these loyal, but poor souls deserve our respect and admiration. So we set out to design the Misery Score to rank those major sports cities where it’s most difficult to keep the faith year after year. We wanted to do this in a rigorous fashion — no punditry or judgment calls — and include all major sports cities in North America.

For this analysis, we considered those cities in the US and Canada with at least three teams in the big four professional leagues (it’s not hard to be bad with just one or two teams; sorry Buffalo and Cincinnati). We weighed playoff appearances, playoff series wins, and championship wins in the Misery Score. We also relied heavily on recent success, since there’s no better way to forget a drought than with a lot of winning (we’re looking at you, Red Sox fans). See the Appendix for details on our scoring system and city clustering choices.

Here, in order, are the top five most miserable sports cities in North America.

1. Cleveland

Cleveland just edges out Toronto for the title of most miserable sports town. Sports fans here are a hardy, but truly miserable, bunch. Without a championship to celebrate since 1964, they have suffered through more shame, embarrassment and heartbreak than fans in any other city. Yet these fans stridently believe that one day, some day, the Cleveland sports curse will finally be lifted.

Cleveland’s past half century in sports is dotted with singular, disastrous events that have become seared in this city’s collective consciousness. Consider Cleveland’s long-suffering football team, the Browns. In the 1981 divisional playoffs, with the Browns needing just a field goal to seal the win, Coach Sam Rutigliano ordered the fateful Red Right 88 play, which led to an interception at the goal line, and the loss; in 1987, with the Browns leading by 7, John Elway and the Denver Broncos miraculously executed The Drive in the final minutes of the AFC Championship, dispensing of Cleveland in dramatic fashion; the next year, once again on the verge of winning the AFC Championship, The Fumble sealed the Browns’ fate in heartbreaking fashion.

But even since these painful heartbreaks, the Browns have also for the most part been just plain bad. The team hasn’t won a playoff game since 1995, and hasn’t won more than 7 games in a season since 2007. And not only have the Browns had trouble winning in Cleveland — they’ve also had trouble staying in Cleveland, as fans suffered the further embarrassment of not fielding a football team at all between 1996 and 1998 after owner Art Modell shipped the players off to Baltimore.

With Cleveland’s basketball team, the Cavaliers, the city has suffered similar bouts of collective misery. In 1989, although the Cavs had swept the season series 6-0 over the Chicago Bulls, Michael Jordan dashed Cleveland’s playoff hopes with The Shot, forever posterizing the city in one of basketball’s iconic moments. Decades later, the NBA’s biggest star and hometown hero, Lebron James, humiliated the city with The Decision to leave Ohio for the balmy beaches of Miami.

It only gets worse. Baseball’s Cleveland Indians have not won a World Series since 1948. The team’s thirty-year slump through the 60s, 70s and 80s inspired Major League, that famous cinematic homage to terrible baseball. The Curse of Chief Wahoo has weakened in the intervening years, but never let up completely: José Mesa’s blown save in Game 7 of the 1997 World Series, and the team’s embarrassing 2007 ALCS loss to the Red Sox after leading the series 3-1, are just the latest in a long line of heartbreak for Indians fans.

With Lebron James’ dramatic return to the city in 2014, there is again hope that the curse will be broken. Cleveland’s future now rests on his shoulders.

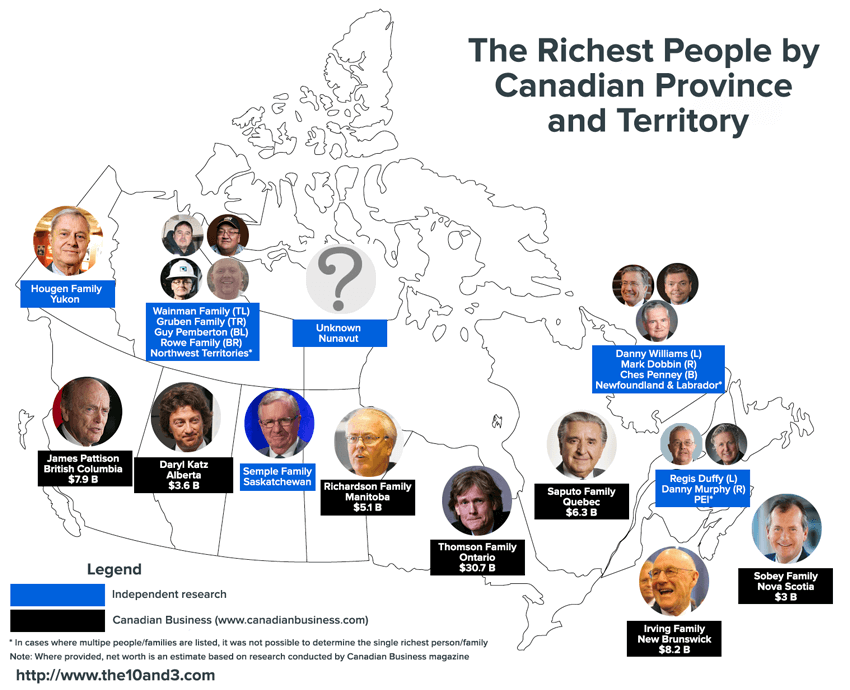

2. Toronto

Whereas Cleveland fans’ suffering has often come through heartbreak — the agony of seeing a championship slip through their fingers — Toronto fans have, for the most part, suffered in a more soul-crushing way. Toronto’s is a grinding, slow-burning torment, the result of year-after-year of losing seasons, poor decisions, and little expectation of future success.

You can’t talk about Toronto sports without starting with the Maple Leafs. The last time the Leafs won a Stanley Cup (and even appeared in a Stanley Cup final) was in 1967, when the NHL had only six teams. Since the ‘04-’05 lockout-cancelled season, the Leafs have made the playoffs just once, in 2013. That year, in the first round, the team managed to squander a 4-1 lead to the Boston Bruins in the final ten minutes of Game 7, and lost in overtime in dramatic (but inevitable) fashion. It was an epic collapse, but just the latest example of the Leafs ability to find new and creative ways to fall out of playoff contention year after year. This season, a once unthinkable series of events has occurred: after years of selling out the Air Canada Centre, fans are finally voting with their feet and deciding not to come; and, for the first time since 1972, the Maple Leafs were dropped from the iconic Hockey Night in Canada Saturday broadcast. Things are glum in Leaf-land.

If you thought it couldn’t get any worse for Toronto sports fans, consider the Blue Jays, who just recently took the mantle of most playoff-starved team in any major sport. The glory of the back-to-back World Series wins in 1992 and 1993 has long since faded, as the Jays haven’t made the playoffs since. Like the Leafs, who occasionally trot out geriatric stars from the 60s for the ceremonial opening faceoff, the Jays try to give their fans a little pick-me-up by showing off their own aging alumni, from Roberto Alomar to World Series hero Joe Carter.

The legacy of the Toronto Raptors is one of excitement but unfulfilled promise. While the team has managed to draft phenomenal rookie talent, including Vince Carter, Tracy McGrady and Chris Bosh, Toronto fans know that inevitably these promising players go looking for greener (i.e., American) pastures. The Raptors may have been fun to watch in the high-flying Vince Carter years, but they were never a serious contender. This year, with a solid roster and celebrity fans like lint-rolling rap star Drake, the team is showing renewed signs of life.

3. New York City (Mets-Jets-Islanders)

It’s not easy being a fan of New York’s “little brother” teams — the Mets, Jets and Islanders — who are forever intertwined by the fate of history and geography (the Mets and Jets long shared a home in Queens’ Shea Stadium, while the Islanders are based in neighboring Long Island). Not only do their bigger, more glamorous New York counterparts (the Yankees, Giants and Rangers) get more than their fair share of attention, they also do more than their fare share of winning. But these proud fans are among the most loyal in sports, and wear their misery as a badge of honor.

The Mets have had only three playoff appearances in the past twenty-six years, and just one in the past fourteen. In 2000, when they finally returned to the World Series, they faced their Bronx rivals in the Subway Series. Needless to say, it didn’t work out in the Mets favor. More recently, the Mets were eliminated from the playoffs on the final day of the regular season in both 2007 and 2008 (their last game in Shea Stadium), and haven’t put together a winning season since.

It’s been a long time since the Jets won the Superbowl, back in 1968. After the team’s low point in 1996 where they notched a dismal 1-15 record, much of the fans’ angst has concerned the parade of uninspiring quarterbacks, who have fizzled out due to injury or poor play. Off the field, former coach Rex Ryan’s storylines — from his ability to overcome dyslexia, his 100-pound weight loss following lap-band surgery, and his widely reported foot fetish — have provided a sometimes welcome distraction from the team’s on-field woes.

For a team that was absolutely dominant in the 1980s (winning four straight Cups, led by the amazing Mike Bossy), it’s been a traumatic fall from grace for the Islanders, who haven’t won a playoff series in over twenty years. Besides being pretty bad on the ice, the Islanders are also known for disastrous dealings off of it, signing ruinous long-term contracts (like Alexei Yashin’s 10-year $87.5M deal and Rick DiPietro’s ridiculous 15-year $67.5M contract) that have severely limited their ability to field a strong team.

4. Houston

It’s been something of a lost decade for baseball fans in Houston, since the Astros peaked in 2005 with their one and only World Series appearance (they were swept in four by the White Sox). That team featured big names like Jeff Bagwell and Craig Biggio in the infield, and Andy Pettitte and Roger Clemens on the mound. The Astros have struggled mightily since then, recording only two winning seasons, and putting together a miserable string of three consecutive 100+ loss seasons. In 2013, the team made the jarring switch over to the American League. Fans and former Astros greats haven’t been happy with the move, but more importantly for the city, it just hasn’t helped the Astros win.

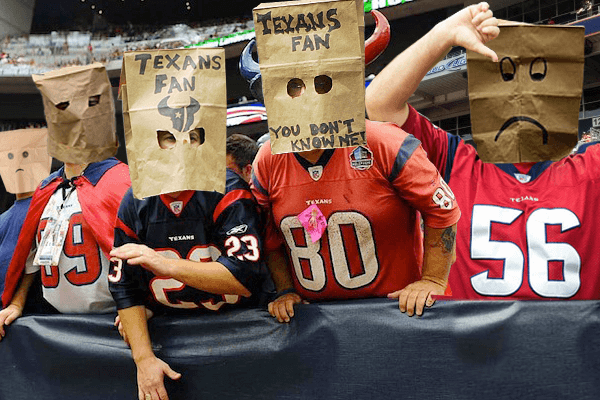

Unfortunately for Houstonians, their football and basketball teams also haven’t given them much to cheer about recently. Football fans suffered perhaps the ultimate humiliation, losing their Oilers, who moved to Nashville in 1997. A lonely five years without football ensued, before the city was granted the expansion Houston Texans. Despite the return of a team, the misery hasn’t let up, with endless losing seasons and only two brief playoff appearances.

Since the Rockets’ magical back-to-back NBA championships in 1994 and 1995, the team has shown several moments of promise, led by players like Yao Ming and Tracy McGrady between 2002 and 2009, and more recently by superstars James Harden and Dwight Howard. Despite the high-wattage names, the Rockets have surprisingly won only a single playoff series in the past seventeen years, leaving fans feeling that they deserve better.

5. Minneapolis-St. Paul

Though all of the Twin Cities’ teams have been reasonably competent at one time or another, they just never manage to break through. It’s the type of misery that makes being a Minnesota pro sports fan a rather frustrating experience.

Take the Twins, the only local franchise to have won a championship (‘87, ‘91). They followed their last Series win with ten straight regular season exits, followed by a decade in which they were absolutely destroyed by the Yankees in the first round of the playoffs on four separate occasions (swept twice, lost 3-1 twice). The Twins have not managed a winning season in the past four years, and the future is not looking bright.

The Vikings have appeared in the Superbowl four times, but the last was almost forty years ago, and of course they’ve never won. A particularly gruesome heartbreak occurred in 1998, when the Vikings went 15-1 in the regular season. In the NFC championship game, the Vikings led the Atlanta Falcons by 7 with just over two minutes remaining. Kicker Gary Anderson, who hadn’t missed a field goal all season, whiffed it from 38 yards; the Falcons miraculously tied the game, and won it in overtime. Vikings fans have never forgotten.

The Wild began as an NHL expansion team in 2000-2001, and have actually been fairly good, making the playoffs on a regular basis. But nobody has ever thought the Wild to be a real contender. It still remains a major point of shame for the hockey-mad city that it managed to lose its beloved North Stars to (of all places) Dallas, Texas, after the 92-93 season.

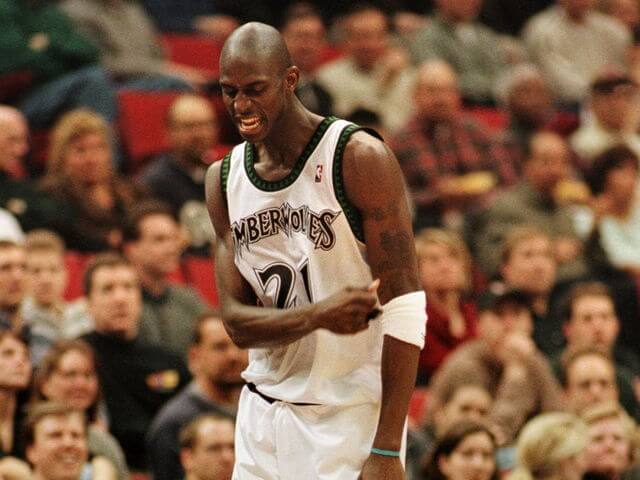

Finally, the hoops-playing Timberwolves haven’t made the playoffs in ten years, but feature some promising youngsters on their roster. The return of Kevin Garnett this season is more symbolic than anything — nobody expects much more than trash talk and a few fierce snarls from KG before he calls it quits — so fans aren’t holding their breath for the bottom-dwelling T-Wolves to emerge as a powerhouse any time soon.

Which city do you think deserves to be in the top 5? Follow us on Facebook or Twitter and join the discussion.

Methodology Notes

Cities with Multiple Teams

Several large cities in North America have more than one professional team in the same league. To handle these cases, we divided fans up into natural allegiances, and calculated separate misery scores for each set of fans. Chicago is an easy one: one set of fans supports the Cubs (Chicago A), while the other supports the White Sox (Chicago B). Los Angeles is similar, with those supporting the Clippers (Los Angeles A) and those supporting the Lakers (Los Angeles B). Anaheim-based teams the Angels and the Ducks are not included due to geography, and since their fan bases are not as readily associated with the set of LA teams.

The San Francisco Bay Area has two football teams and two baseball teams (and a single basketball and hockey team). Those in the East Bay back the Raiders and Athletics (San Francisco Bay Area A), and those in SF and the peninsula back the 49ers and Giants (San Francisco Bay Area B).

Finally, there is the complexity of New York City. There are of course many exceptions to the clustering that we selected, but generally speaking, we have the “big brother” and “little brother” teams of New York. The Rangers and Knicks (who both play in Madison Square Gardens), along with the Yankees and Giants, have a somewhat consistent fan base (New York City A). Similarly, the Jets and Mets (who shared Shea Stadium in Queens), along with the New York Islanders (who are from neighboring Long Island), tend to share fans based on geography and a common history (New York City B). We omitted from our analysis the New Jersey Devils, as well as the Brooklyn Nets (who may still be finding a consistent fan base after moving from New Jersey).

The Misery Score Explained

We first compute a misery score for each team, as follows: a team gets a demerit point for each year since (i) it last made the playoffs, (ii) it last won a playoff series (which doesn’t include MLB play-in game wins), and (iii) it last won a championship. We cap each of the three above point values at 30, because the average fan’s age in the major sports is approximately between 42 and 43, and the age of 12 or 13 is the general age of enlightenment when fans start to really understand sports (and the misery that comes with losing). These points are added together, which gives each team a number of points between 0 (if the team won a championship last season) and 90 (if the team hasn’t made the playoffs in the past 30 years); we then normalize these values onto the [0,100] scale, to get a team-level misery score.

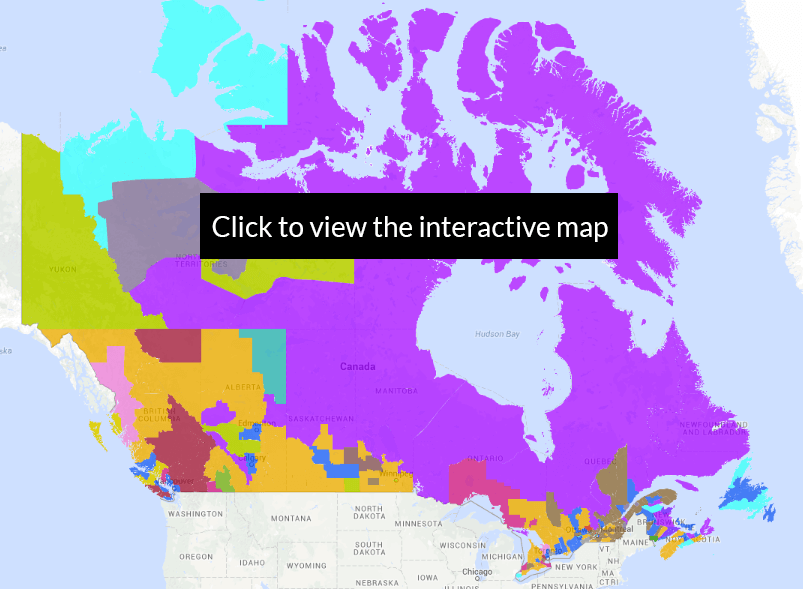

Finally, for each city, we take a simple average of its component teams’ misery scores, to get an overall city-level misery score. For ease of interpretability, we bucket these city scores into 4 categories: green (0-15), yellow (15-30), orange (30-45) and red (45+). Green means that you only need to look back, on average, about 5 years to see a lot of success (Boston); yellow look back 10 years (St. Louis), orange look back 15 years (Atlanta), and red over 15 years (Cleveland, Toronto and New York City B).

Note that we have only chosen to display NFL champions since the first Superbowl (in 1967). Teams with their last win prior to that (ex. Detroit) are marked as “NA” in our graphic.