As the water contamination crisis in Flint, Michigan has exploded over the past year, residents of cities across North America have increasingly wondered about the safety of their own municipal tap water. In some places in Canada, they have good reason. Worries about Flint-like lead contamination have authorities redoubling efforts to examine aging water infrastructure. Memories of the disastrous Walkerton E. coli crisis in 2000 are still fresh in people’s minds, and to this day, there are roughly 1000 active boil-water advisories at any given time across the country. Combine that with persistent (though scientifically unsupported) concerns about the health effects of fluoridation, and it becomes clear why Canadians in some parts of the country choose water from the bottle rather than the tap.

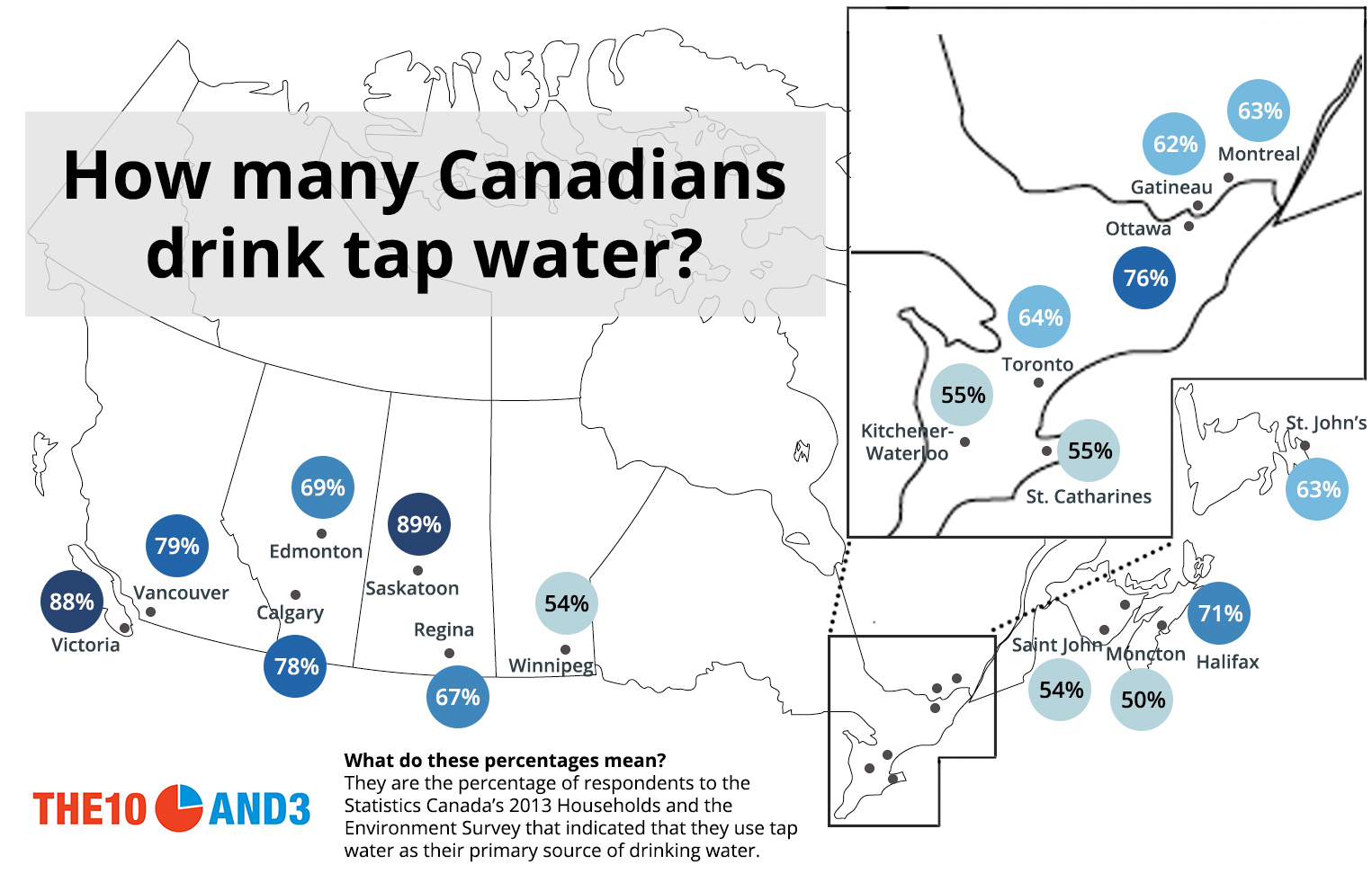

The data shows that while approximately two thirds of Canadians use tap water as their primary source of drinking water, in some major cities almost half of residents avoid tap water for their primary drinking needs. Though the country’s municipal water systems are generally considered of high quality overall, the numbers suggest that in many communities there is a deep distrust in the safety of drinking water.

When the Water Turns Brown

When brown water started emerging from taps in Winnipeg in 2010, residents of Manitoba’s capital were understandably alarmed. The city ordered an investigation to determine the cause of the discolouration, but brown water persisted in some areas throughout the city for the next several years, and spiked in the summer of 2013. The city finally determined that high levels of manganese, a potential neurotoxin at high concentrations, may be to blame. But guidance from city hall on the safety of the drinking water has nevertheless been confusing. On one hand, the city appears to be playing down any serious health risks, noting that “discoloured water can result from routine operations,” and appears to suggest that the main reason residents should avoid using discoloured water is because it “does not taste, smell or look pleasant, and it can stain clothes.” On the other hand, the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority is much less equivocal, advising residents unambiguously to avoid drinking the brown water or using it for food preparation.

Reports of brown water from frustrated Winnipeggers have periodically continued through 2015, which helps explain why Winnipeg’s rate of tap water consumption (54%) is among the lowest in Canada.

Boil-Water Orders Across the Country

Ottawa and Gatineau may together form the core of the National Capital Region, but they may as well be in different countries when it comes to drinking tap water. While Ottawa’s tap water is generally considered of very high quality, Gatineau, which has a separate municipal water system from its neighbour, has been plagued with numerous boil-water advisories over the past years, leading to far fewer of its residents (62%) relying on tap water.

In many parts of the country – including a disproportionate number of First Nations communities — boil-water advisories are simply a fact of life. Saint John, New Brunswick, the second largest city in the Maritimes, has been plagued by boil-water advisories for years. Recently, part of the city’s water supply has been transitioned from lake water to well water, an advance which the city promises will bring better tasting, better smelling, and most importantly, safer water to residents. With only 54% of Saint John residents relying on the tap for their source of water, it remains to be seen whether these changes will increase trust in the municipal water system.

Lead Pipes

The crisis in Flint has led many in Canada to wonder whether old lead pipes may be lurking in our aging water infrastructure. In 2007, Ontario ordered an inspection of old homes across the province for potential lead contamination after surprisingly high levels were discovered in London. As reports started coming back that some homes in Sarnia, Hamilton and Owen Sound measured lead levels above the provincial standard, cities and towns across the province instituted rigorous inspection procedures – particularly in older homes – to discover and correct problems early. Nevertheless, with lingering concerns about lead and the Walkerton E. coli crisis still a recent memory, a meager proportion of residents in many of Ontario’s smaller cities like Kitchener-Waterloo (55%), St. Catharines (55%) and Peterborough (58%) appear ready to fully embrace tap water as their primary source of drinking water.

Methodology

Drinking water habits were gathered from Statistics Canada’s 2013 Households and the Environment Survey. In this piece, we use the figures which indicate what percentage of residents use tap water as their primary source of drinking water. The survey also provides data for the percentage of people who rely on bottled water, a combination of tap and bottled water, or other sources, as their primary source for drinking water. We note that data for the combination of tap and bottled water case was often deemed unreliable by Statistics Canada, which is why we focused on tap water only.

Don’t miss our newest stories! Follow The 10 and 3 on Facebook or Twitter for the latest made-in-Canada maps and visualizations.