In 1992, Maria Shepherd pled guilty to a crime she didn’t commit: killing her three-year-old stepdaughter. Her lawyer told her she didn’t stand a chance against the testimony of renowned pathologist Charles Smith. Knowing she could spend years in prison away from her young children if she fought and lost her case, Shepherd pled guilty to manslaughter and lived with a wrongful conviction on her record for 25 years.

Thanks to the lawyers who worked on her behalf and a public inquiry that discredited the doctor, Shepherd’s wrongful conviction was finally overturned in 2016 on appeal. Although she only spent eight months in prison, less than half of her two-year sentence, the consequences of her wrongful conviction stayed with her for decades.

“It really does rob you of your mental health,” says Shepherd, who had three children under the age of five and was pregnant at the time of her incarceration. Shepherd says she pled guilty out of fear that she could lose custody of her children if she were incarcerated for years instead of months.

The clinching detail in Shepherd’s case, later found to be unsubstantiated, was a bruise on three-year-old Kassandra, which Smith said matched her stepmother’s watch and was evidence of a fatal blow. But the inquiry into Smith’s forensics found that his background in forensic pathology was severely lacking and that many of his conclusions on the stand were unsupported by science, contributing to other wrongful convictions in addition to Shepherd’s.

After spending less than a year behind bars, Shepherd was released to a halfway house just weeks before the birth of her daughter. She remembers barely holding her newborn before the child was taken out of her hands. Years after her release, Shepherd recalls her children being taunted at school because of their mother’s label as a “baby killer.”

Innocence Canada, an organization that works to exonerate the wrongly convicted, helped overturn Shepherd’s wrongful conviction. In fact, over the last three decades, the organization’s pro bono work has helped exonerate a significant number of Canadians who have been wrongly convicted.

Win Wahrer, the cofounder of Innocence Canada, says she has seen a variety of factors that have resulted in wrongful convictions over the years. These include eyewitness errors, false confessions, or, as in Shepherd’s case, plea bargains.

Wahrer says wrongful convictions can also happen due to systemic issues like tunnel vision, jailhouse informants, and “junk science” – an epithet often applied to Dr. Smith’s faulty forensics. Despite the varied reasons that may lead to a wrongful conviction, what the cases have in common is that they are usually waiting games.

Although Shepherd’s wrongful conviction was overturned on appeal, sometimes appeals can serve to cement a wrongful conviction instead of correct it. In these rare cases, the wrongly convicted lose their appeals.

Recognizing this possibility for gross injustice, the Department of Justice has established a review process for people who have been wrongly convicted even after an appeal. These individuals can apply for ministerial review to get a new appeal or—in cases involving more egregious miscarriages of justice—a new trial.

According to the Department of Justice, “[w]hen an innocent person is found guilty of a criminal offence, there has clearly been a miscarriage of justice.”

Applicants seeking to have their case reviewed must show “important new information or evidence that was not previously considered by the courts” to prove a miscarriage of justice occurred. Sometimes this important new information is the result of DNA evidence or a witness with new details.

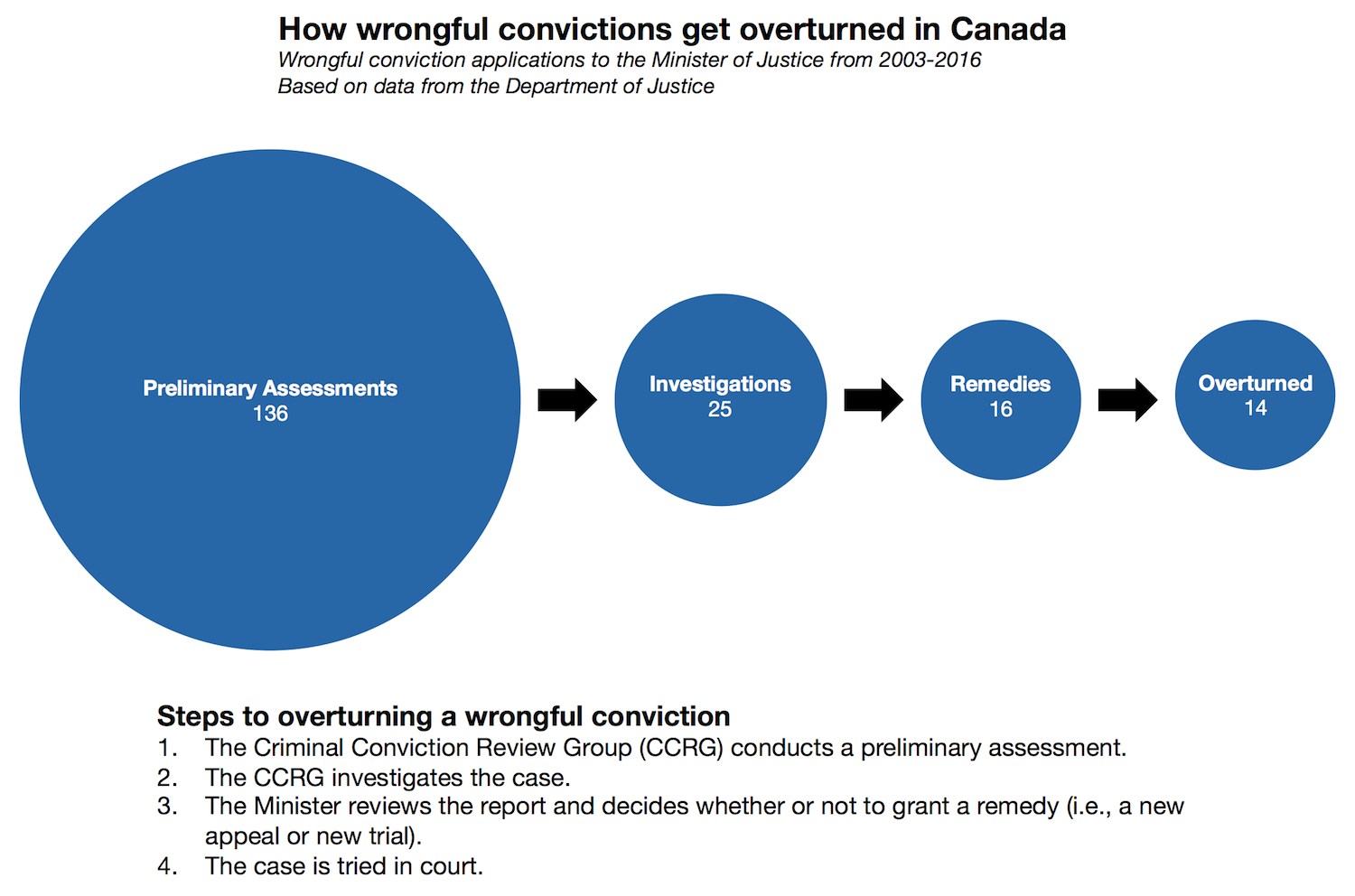

Steps to overturning a wrongful conviction after losing an appeal

While the road to exoneration may be long and winding, the destination is desolate. The last 15 years of data from the Department of Justice show that the vast majority of ministerial review applications are unsuccessful.

Innocence Canada has helped many individuals overturn their wrongful convictions via the ministerial review process and the courts. While a miscarriage of justice is not synonymous with innocence, Wahrer says, “Generally speaking, we believe the clients we take on are innocent. Not only that, you have to have substantial amount of evidence to convince the justice minister to reopen a case.”

Some cases could take years to compile new information before they are even submitted to the ministerial review process.

“We had a case since the 1990s, and we just submitted an application last year,” says Wahrer. “You have to make sure you have enough information, enough evidence, to support your claim on behalf of your client.”

Working for the Department of Justice, the Criminal Conviction Review Group (CCRG) is tasked with reviewing the cases, which could involve a variety of offenses under the Criminal Code. But Kerry Scullion, one of four lawyers that form the CCRG, says most of their cases are murders.

The current criminal conviction review process has been in effect since 2002. Scullion says he believes the current process was a response to the high-profile case of David Milgaard—who spent more than two decades behind bars before being exonerated—and other public inquiries into major miscarriages of justice.

The road to overturning a wrongful conviction is a four-step process. A successful application will first undergo a preliminary assessment, then an investigation, followed by a recommendation from the CCRG, and finally, a decision from the minister. After these four steps, the case reenters the court system.

In order for a case to get a preliminary assessment, however, the applicant must submit “important new information,” or fresh evidence that was never considered by the courts to show they have been wrongly convicted.

Scullion explains that the preliminary assessment involves looking at the credibility of the new information and whether it would affect the outcome of the case, or as he says, determining “if there’s smoke.” For example, a case that relies on the testimony of a new witness with a long rap sheet may require more discovery at the preliminary assessment stage before the case is determined credible, says Scullion.

According to data from the Department of Justice, most cases fail to make it past the first stage. A total of 136 preliminary assessments have been conducted since 2002, but only 25 cases have made it to the next stage – the investigation stage.

“Most cases don’t make [it] to the investigation stage because they have no merit for a variety of reasons,” says Scullion.

For the cases that make it to the second stage, Scullion explains, the investigations often involve “digging deeper” into the new information, which may include examining recanted witness testimony or new DNA evidence, especially for older cases where DNA testing was unavailable.

Yet despite the renewed popularity of shows like “Forensic Files” that portray DNA evidence as the holy grail of vindication data, Scullion cautions that DNA is only available in a small number of cases. “It’s not the panacea that it’s made out to be.”

The entire ministerial review process could be done in a matter of weeks, but the more serious cases take years, says Scullion, as the CCRG lawyers must wait for and dissect new information.

“These cases need to move faster than they’re moving,” says Wahrer, citing a current Innocence Canada client whose case has been in the ministerial review process for four years now. Unfortunately for the innocent, it can take a long time for potentially exonerating evidence to surface and to undergo a thorough investigation. In the meantime, applicants may be left in limbo.

After they complete their investigation, the CCRG prepare their report and present their recommendations to the minister, who then decides whether to grant a new trial or not. Out of the 28 cases that the minister of justice has reviewed since 2002, 16 trials have been granted, 14 of which resulted in the conviction being overturned; the remaining two cases are still before the courts—the last long step to overturning a wrongful conviction.

As for preventing major miscarriages of justice in the first place, Scullion says that police have implemented some new changes to prevent wrongful convictions, such as audio- and video-recording confessions.

But Wahrer believes more could be done to prevent wrongful convictions in Canada. “Most people involved with a wrongful conviction are rarely ever held accountable,” says Wahrer.

While it is impossible to know how many innocent people are behind bars in Canada, it is clear that wrongful convictions do happen, and for people who get a chance at exoneration, their cases often take a lot of hard work — and hard time — to reverse.

Although Shepherd’s case did not go through the ministerial review process, she understands the stress that comes with waiting for exonerating evidence while living with a wrongful conviction. “It doesn’t matter how much you try to have hope,” says Shepherd, “when you feel like your story’s never going to be listened to and nobody’s ever going to care about hearing the truth, your hope slowly dies.”

The biggest change for Shepherd since being exonerated is that she was able to become a licensed paralegal, a designation that her conviction had precluded.

Having lived half her life with a wrongful conviction, she now helps to spread the word through her advocacy work about how wrongful convictions can happen to anyone. “The system can take your freedom from you and you can allow it to destroy you,” says Shepherd. “Or you can take your experience, turn it into something positive, and work in the system to try and make corrections.”