Today, one of the largest strip clubs in Etobicoke, the westernmost borough of Toronto, has become a gourmet burger restaurant. The vestiges of its past as a bar where men would visit to watch scantily clad women and drink beer have been replaced by family-friendly menus and waiters dressed in t-shirts and jeans, while the blacked-out windows have given way to an open, airy interior.

The story is the same in many places across English Canada. Strip clubs were formerly a mainstay of Canadian life, frequented by groups of younger men out on the town, and older men looking to blow off steam after work. But today, the story is bleak for the once thriving industry.

The Numbers

The clubs tend to fall into two broad categories. There are the downtown clubs, such as the Brass Rail on Yonge Street in Toronto, popular with tourists and bachelor parties, and those in the suburbs, often in unassuming strip malls and featuring ads for food and drink specials on the front door. While the downtown clubs are certainly in decline, this second group has been hit even harder by changes in law, demographics, and culture that have widely put the entire industry on a downhill trajectory. The industry group overseeing strip clubs, the Adult Entertainment Association of Canada (AEAC), evaporated within the last year amid infighting and a rapidly changing environment.

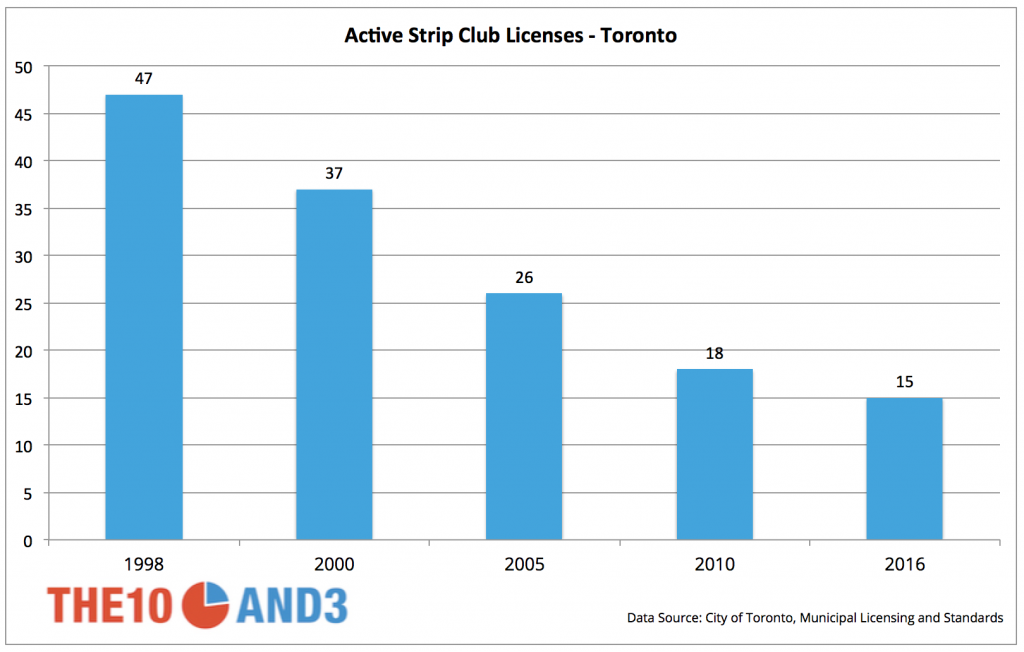

Across Ontario, there are fewer strip clubs than ever before. Toronto has seen the starkest downturn. In 1998, the first year after Toronto’s amalgamation, there were 47 active strip club licenses within the city. Today, only 15 remain – and they operate out of just 13 buildings. This experience has been mirrored across the country as some cities have seen their strip clubs wiped out completely.

The Law

Canada has had a checkered history with strip clubs, and some of the most vigorous constitutional debates have stemmed from their operation. Starting with Canada’s first completely nude strip club, the aptly-named Pandora’s Box in Ottawa, litigation over the right of these clubs to operate ran throughout the 70s and 80s. The courtroom debate centred around just how much patrons can see – and touch. Today, the law stands that stripping is constitutionally acceptable, but provinces and cities can regulate strip clubs via nuisance laws.

This has led to some extreme situations. In Saskatchewan, the legislature has flip-flopped on allowing licensed strip clubs to exist at all. The province had previously never legally permitted strip clubs wherever alcohol is served, but decided to give it a shot in 2014. During the small window of legalization, strip performances were permitted twice per month at certain bars, and required frequent police checks and screening processes.

Historically, without specific clubs in the city, Saskatoon would issue licenses directly to each dancer, who were required to keep them during their shifts. In 2014, when stripping was legal, the number of licenses in Saskatoon ballooned to 53, for the city of 222,000.

But less than two years later, Saskatchewan quickly re-enacted its ban, citing a fear of increasing organized crime and exploitation of young women. By the end of 2015, only five licenses remained valid. The political drama created an uproar in Saskatoon, the province’s largest city. These days, the only time stripping is legal in Saskatchewan is for a charity event.

“I’m very unimpressed with the way people view the industry, and the way they see us,” said Tokyn Thompson, a current dancer and the former owner of the Tiger Lily Cabaret in Saskatoon. “We’re still educated, intelligent, and still human, and it was really hard reading what people say about you, and what people assume about you.”

Thompson was among an industry group that fought the ban’s reinstatement. After multiple hearings and meetings, the law was eventually changed to rein in stripping in the province. Consequently, Thompson’s performances in bars had to stop, and she was also barred from performing at private parties, previously the lifeblood of her business.

“We had a good thing going on and we were working with the police. [Proponents of the change] were using a lot of hot-button words like child exploitation and human trafficking, but it was good, we kept underage girls out of the industry,” said Thompson. “I’m not a mob boss, I own a company, and I was the only game in town.”

“The thing is, when you can only do it for charity, and it’s so heavily regulated, then it’s no longer an industry,” added Thompson, who has been forced to find new work after deciding to stay in Saskatoon. Other performers have uprooted their lives completely for Manitoba or Alberta.

While Saskatoon stands as an extreme example, a checkerboard of laws and regulations, at the municipal, provincial and federal levels, govern the operation of these clubs around the country. Occasionally, the results are laughable. Manitoba laws state that dancers must have the majority of their buttocks covered when not dancing on the main stage. Toronto requires all strip club managers to be “neat and clean in his or her person and civil and well-behaved.” London, Ontario, specifically disallows any more than four strip clubs from operating within the city.

The Business

But the laws are serious business, and they have barred the industry from recruiting new talent, operating close to residential neighbourhoods, and in some cases, turning a profit.

“Strip clubs are in decline. It’s not a good business anymore. It was a good business, but not as much now,’ said Spiro Koumoudouros, owner of both the House of Lancaster and House of Lancaster II, in Toronto. Koumoudouros is among the last businessmen who own multiple clubs in the city.

While Toronto’s clubs have not fared well, other smaller markets have faced unique challenges relating to the patchwork of laws each province operates under.

“Our liquor laws [in Manitoba] say you need to have a hotel before you can have a strip club,” said Rick Irving, founder of Superb Entertainment, which books dancers throughout Manitoba and Northwestern Ontario. “When we started the business 50 years ago, every hotel had dancers.”

Irving estimates that there are over 100 hotels in Manitoba that were booking his dancers. He says that even in the large area he works from, business has dropped off precipitously within the last decade.

Circumstances are just as tough in smaller Ontario markets too. In 2000, London, Ontario had six operating strip clubs. Sixteen years later, only three clubs still operate for the city of 475,000 after one club had its liquor licence revoked for potential ties to southwestern Ontario biker gangs.

Strip club owners have in the past attempted to band together to lobby all levels of government for more favourable regulations. However, its industry group, the Adult Entertainment Association of Canada (AEAC), folded within the last year due to infighting and economic pressures.

Koumoudouros, particularly, has trouble attracting new employees to work for him, and he sees this as the result of both federal and municipal policies working against him. The two prongs of law and policy stem from changes to federal immigration procedures, and the evolution of a more permissive attitude towards massage parlours.

If someone wants to become a stripper in Toronto, they need to go through a police background check, and their position as a stripper will re-surface on future background checks. As with other service industry work, like bartending and pouring lattes, few intend on stripping for an extended period of time. The legal implications mean that few locals are willing to select this work over other service industry positions.

“The only way this business can survive is if the federal government allows us to import entertainment,” says Koumoudouros. “The federal government stopped allowing work visas … There are no entertainers – people can’t watch the same, the same, the same.”

Koumoudouros also claims that legitimizing body rub parlours – colloquially known as “rub and tugs” – have attracted the labour pool elsewhere. Today, the operators of these establishments can receive licensing from the city and operate as a business under similar bylaws to strip clubs.

“Massage parlours have always been an even thornier issue than strip clubs,” said Rudi Czkella-Martinez, a former consultant with the AEAC and author of several reports on the state of municipal zoning within the Adult Entertainment Industry. “The strip club industry doesn’t get along with the body rub community. Strip clubs have always argued that they shouldn’t be allowed, and that they’re brothels.”

Throughout the last 25 years, zoning regulations have forced new strip clubs to open in industrial areas, away from residents and similar businesses. Meanwhile, massage parlours, escort services, and online entertainment flourish closer to home. In today’s environment, if you want to visit a strip club, you need to work to get there.

So who, exactly, is still willing to do just that?

The People

One would assume, with an aging male demographic in Canada, that strip clubs wouldn’t have any issue filling their bar stools. But as the laws have changed and more edgy, sex-driven businesses have opened up, competition for this sort of money has become fierce.

“Strip clubs are almost like quaint businesses now,” lamented Czkella-Martinez. “They hit their heyday in the 80s, back when they were seedy and edgy, and now it seems that they can’t compete. You sit there, you order a beer, and you see who’s around. It’s not like in the 80s when it was crazy.”

Perhaps the biggest incoming threat to the business model is coming from online pornography. The porn industry worldwide has been valued at $97 billion, a bigger entertainment market than the three largest North American professional sports leagues combined. The breadth of video, photography, and interaction online lets consumers find precisely what they’re looking for, and in some cases, the interaction from within the home creates an environment similar to what would be found at the neighbourhood strip club.

“The general feeling is that it’s mostly men using these sites, and websites cater to them, but it’s sort of a chicken-and-egg problem,” said Patrick Keilty, a professor at the University of Toronto who studies the information technology of online pornography. “There’s a privacy element, and that creates a kind of comfort. Things like porn, dating apps and online escort services allow for people who would otherwise be shy to do these things from home.”

While this sort of experience can be found at anyone’s fingertips, it remains unclear whether users of online porn are identical to those who used to frequent strip clubs. The largest online porn companies, like PornHub, collect vast tracts of user data about who frequents their network of sites, but that data remains largely proprietary and it remains difficult from a statistical standpoint to parse out demographic data from this information.

“Companies like PornHub are really a medium-sized tech company,” said Keilty. “They’re not just interested in where you go on their site, but where you go after as well … it’s driven heavily by advertising.”

Although the online world can approximate the experience of seeing a stripper live, it’s still not a perfect substitute. It’s unsurprising, then, that porn theatres have gone extinct far faster than even strip clubs; the last remaining porn theatre in Toronto recently closed, and the space was quickly replaced by a rock climbing gym.

“To be quite honest, the impact of zoning and licensing haven’t been as great as people would think,” said Czkella-Martinez. “A lot of the reason why these businesses have been going down and down is what’s going on in society in general.”

The public’s perception of strip clubs hits home especially for Koumoudouros, the Toronto club owner, who saw deliberate attempts to remove him from chairing the board of the business improvement area in his neighbourhood.

Strip clubs are not necessarily dead, in fact, but are instead working on adapting to new clientele. The best example of this adaptation can be found in Edmonton. Unlike the prohibitionist approach adopted by its provincial neighbour to the east, Edmonton strip clubs have continued to press onward. Only one strip club license has been outright cancelled within the last decade. While clubs are closing every year in Toronto, two of them opened in Edmonton in 2013. Meanwhile, Pinky’s Show Theatre recently took over another strip club, and re-launched this March, making it the newest strip club in Canada.

Successful clubs are relying less and less on the shock value of its entertainment. Instead, they’re attempting to re-focus as a party atmosphere, with the dancing girls serving as a backdrop and a part of a larger nightclub.

Nevertheless, it remains to be seen if they can survive outside the tourist campiness on Toronto’s Yonge Street or Montreal’s Saint Catherine Street. It seems strange to lament the loss of an industry that so many have derided over the course of history, but for many, the strip club world served as a livelihood, work experience, and sometimes, even great memories.

“There wasn’t a ton of us in Saskatchewan, so we all became a family,” reminisced Thompson, recently speaking from a bus to Winnipeg to perform there once again. “I miss it.”

Don’t miss our newest stories! Follow The 10 and 3 on Facebook or Twitter for the latest made-in-Canada maps and visualizations.