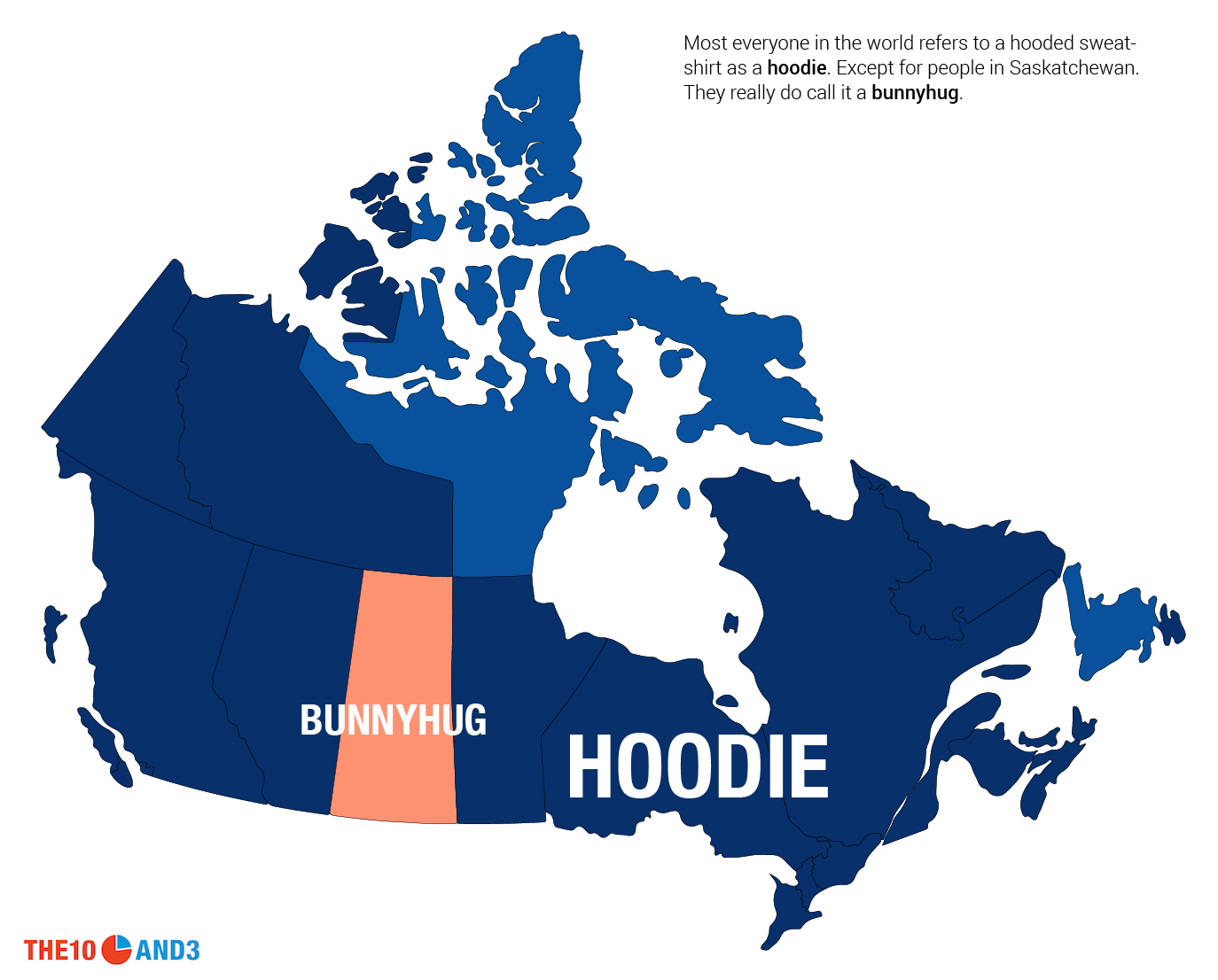

Spread across a vast landmass, Canada’s roughly 30 million anglophones speak something called Canadian English. The stereotype often goes that Canadian English is a lot like American English in terms of both vocabulary and pronunciation, with significant influence from the British Isles, resulting in words like zed and spellings like colour and centre. A subtle Canadian accent that affects the vowels in words like about and write, and a collection of characteristic Canadian vocabulary like chesterfield, toque, poutine and bunnyhug, add to its uniqueness.

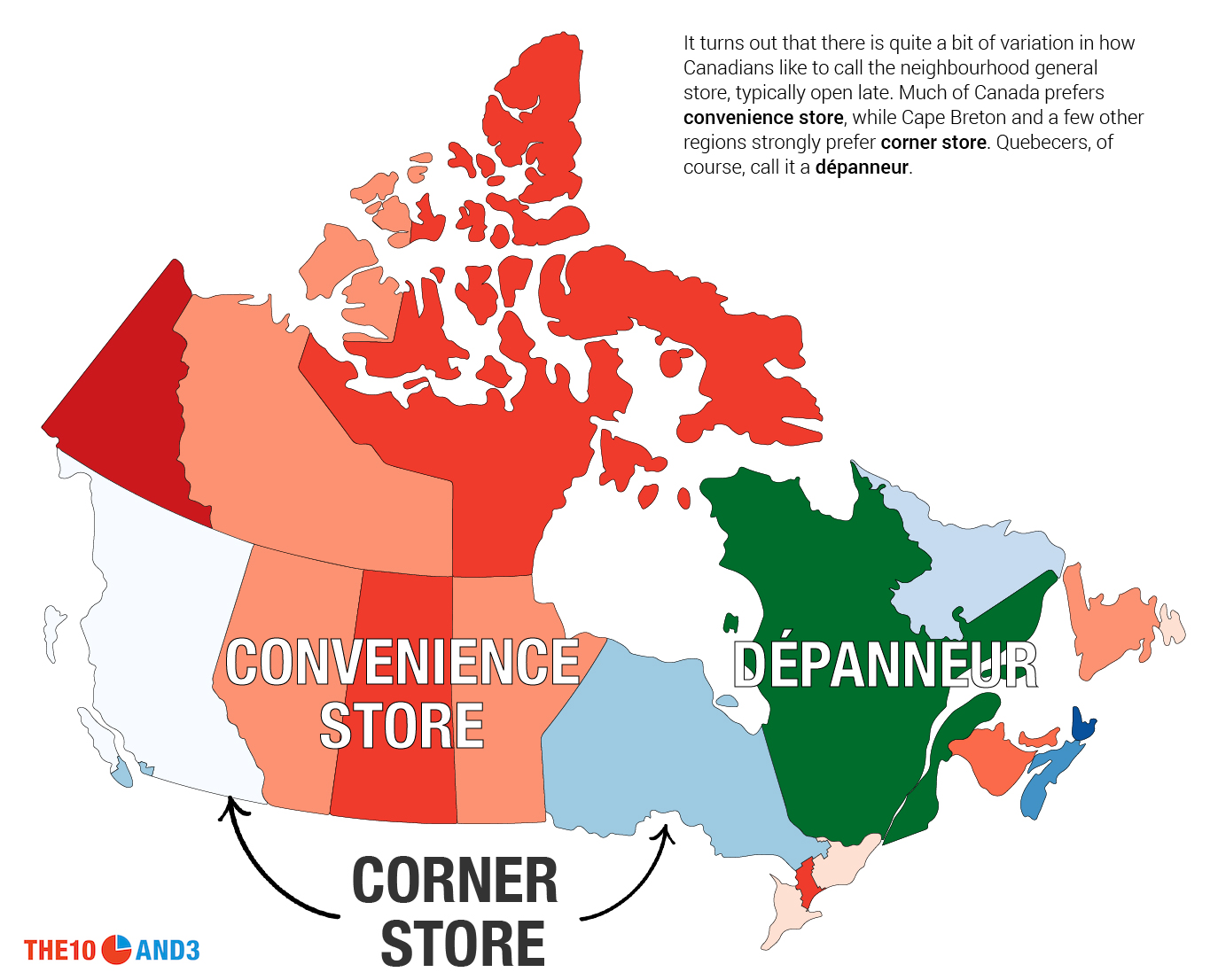

Wait, bunnyhug? Yes, bunnyhug is a very Canadian word (for a hooded sweatshirt), but you’ve probably never heard of it if you live outside of Saskatchewan. It turns out that there is a surprising amount of diversity within Canada when it comes to how we talk and the words we use. Of course, everyone knows about the characteristic English of Newfoundland, and regions like Cape Breton, Lunenberg and the Ottawa Valley also have unique ways of speaking. But even in other places that have no obvious reason to talk differently, Canadians have developed strong regionalisms.

Charles Boberg, an Associate Professor of Linguistics at McGill University, suggests that in addition to the influence of French as well as historical settlement patterns, much of our country’s language regionalism is due to “simple isolation.” While we can now easily communicate and interact with Canadians from all corners of the country, that was obviously not always the case. “[With] a relatively small population spread out over 5000 km … local cultures, which include unique vocabulary, have a chance to develop in each region, even over the relatively short time span of one or two centuries, without diffusing to other regions.” This isolation has given rise to some fascinating linguistic trends.

The Survey

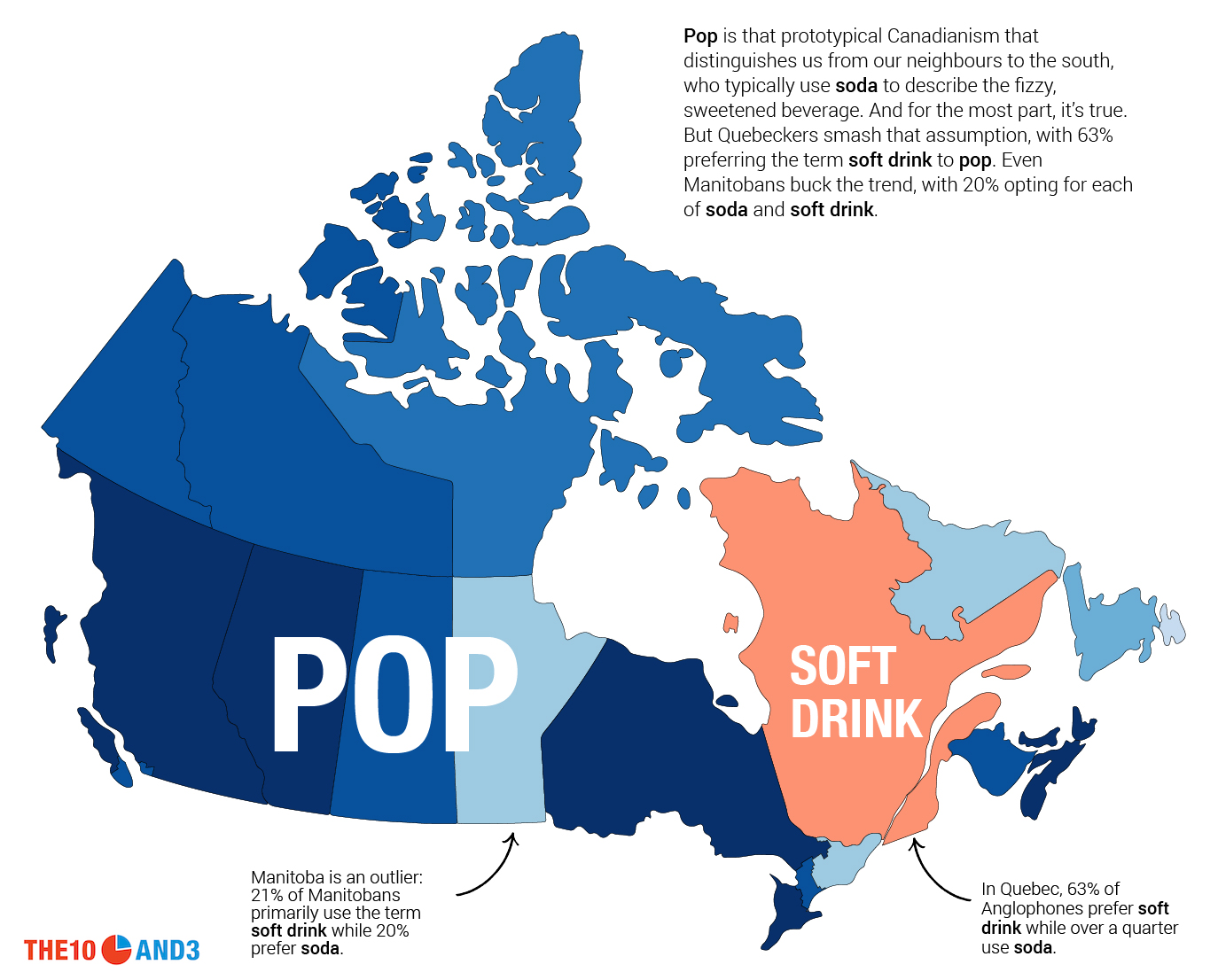

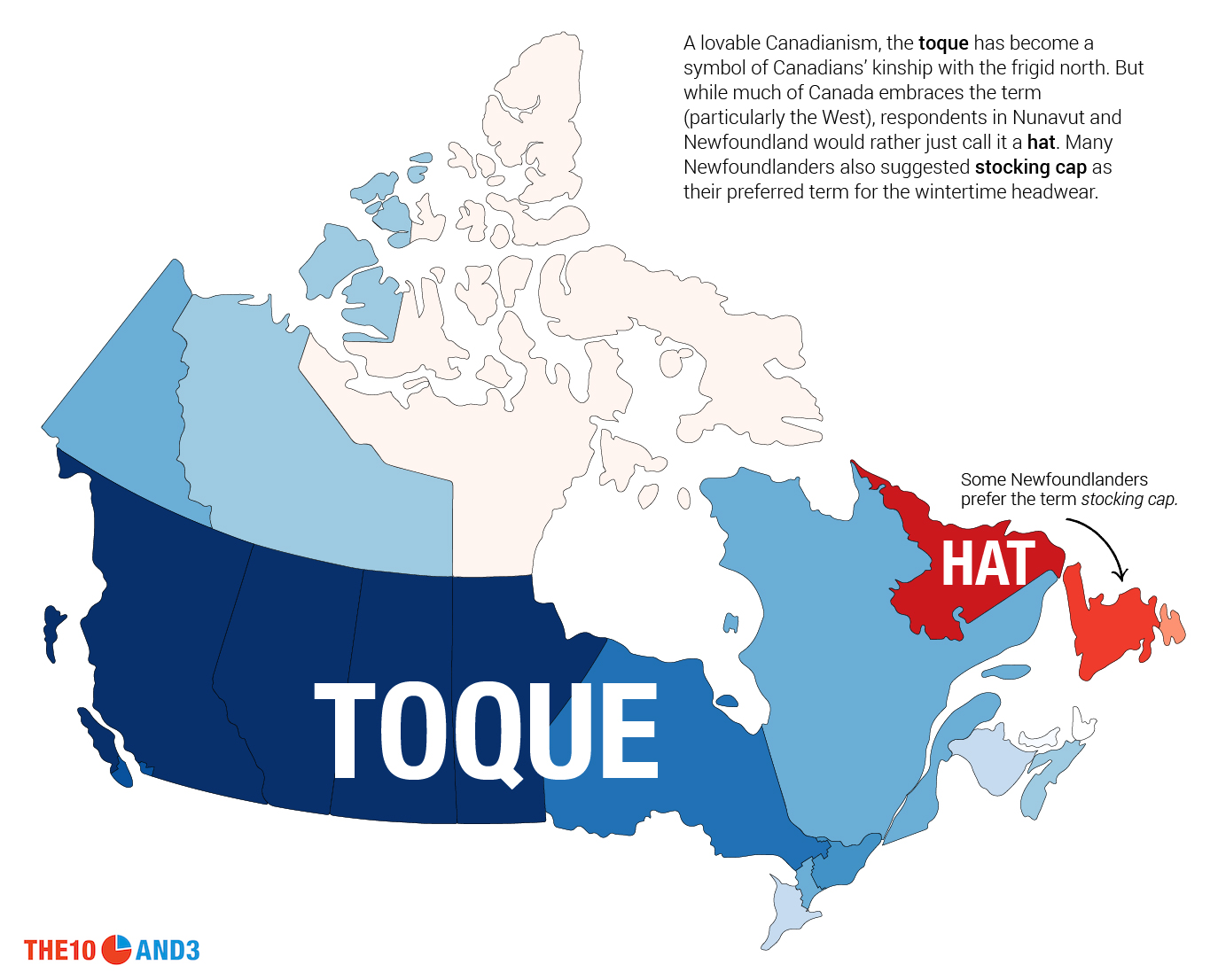

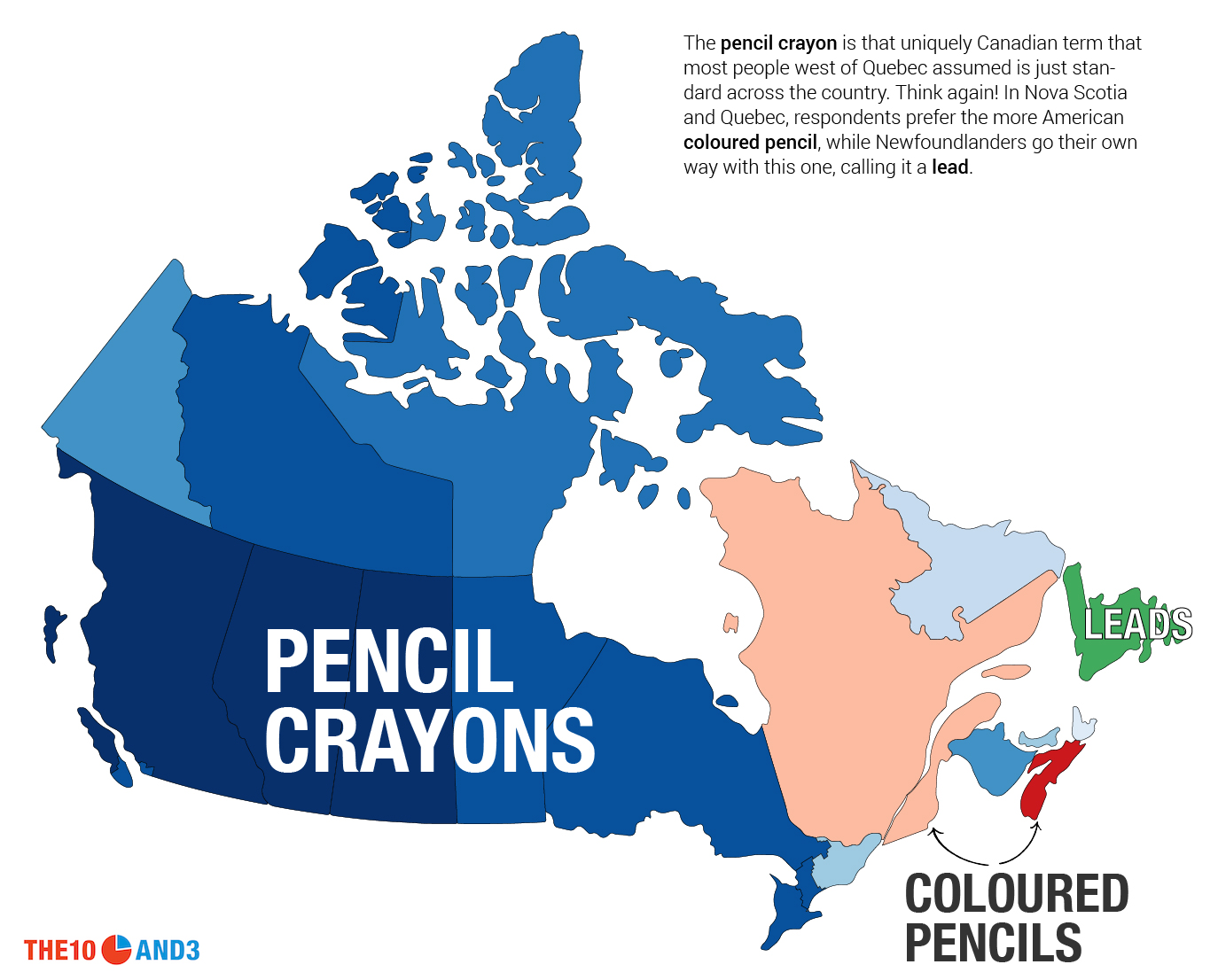

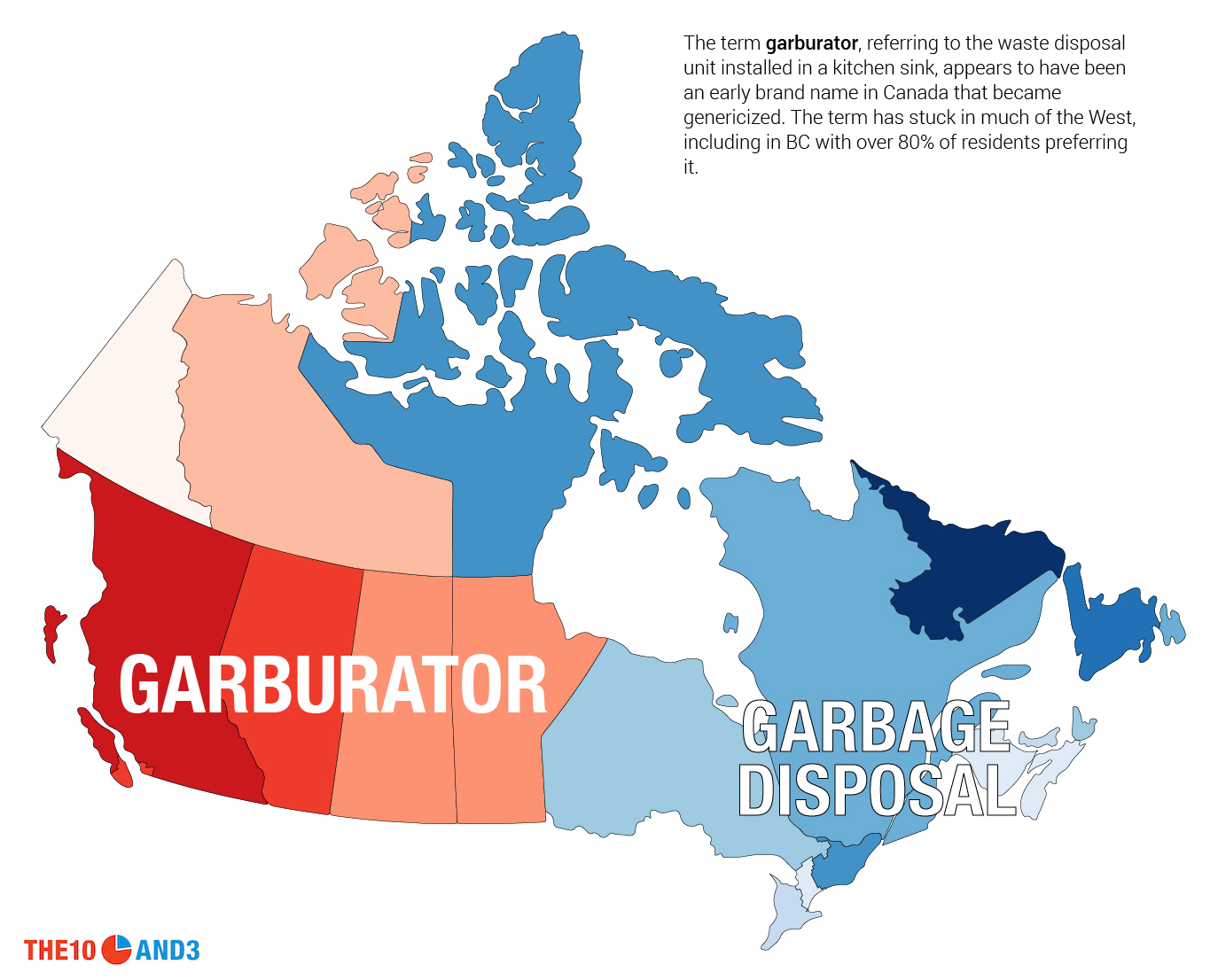

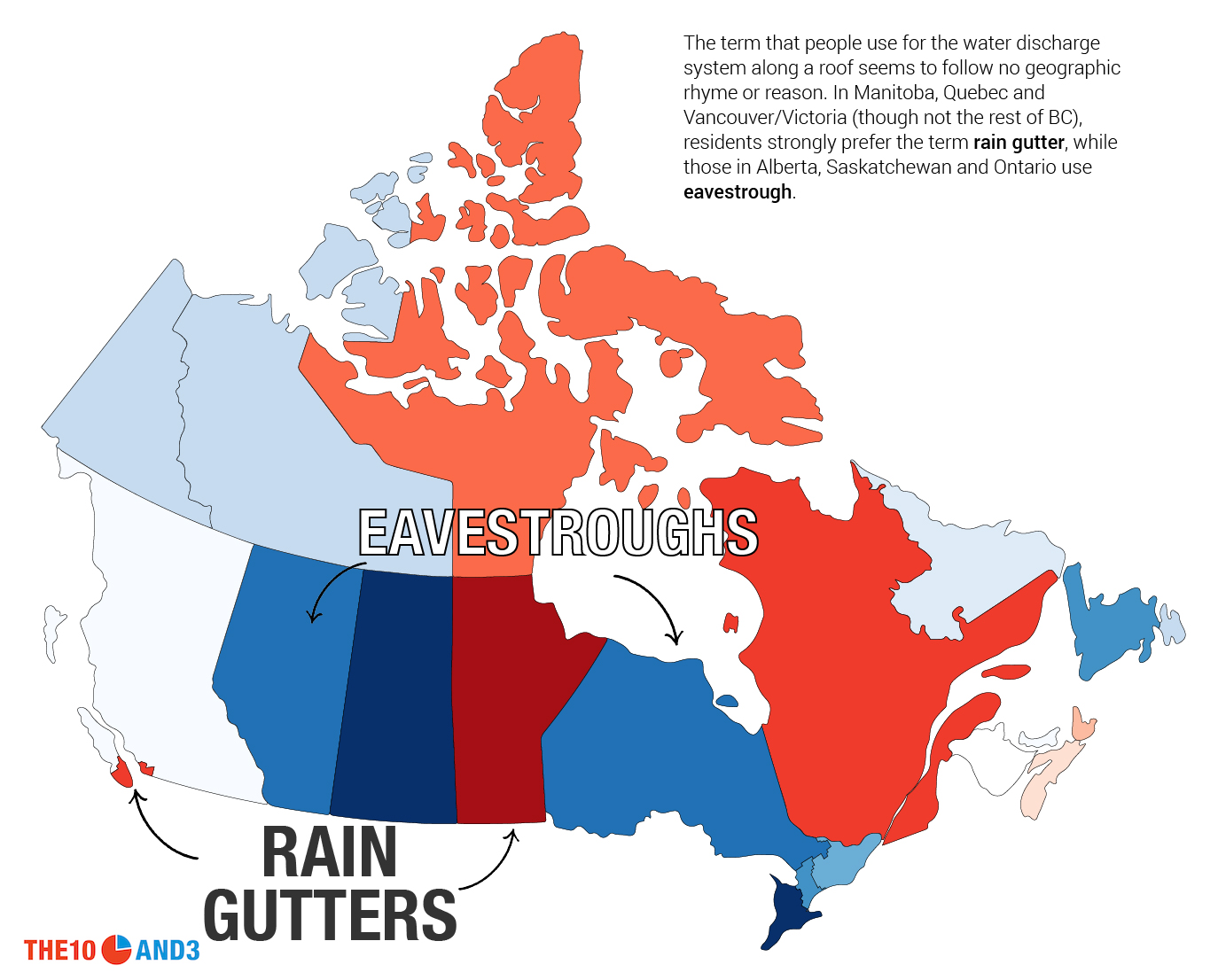

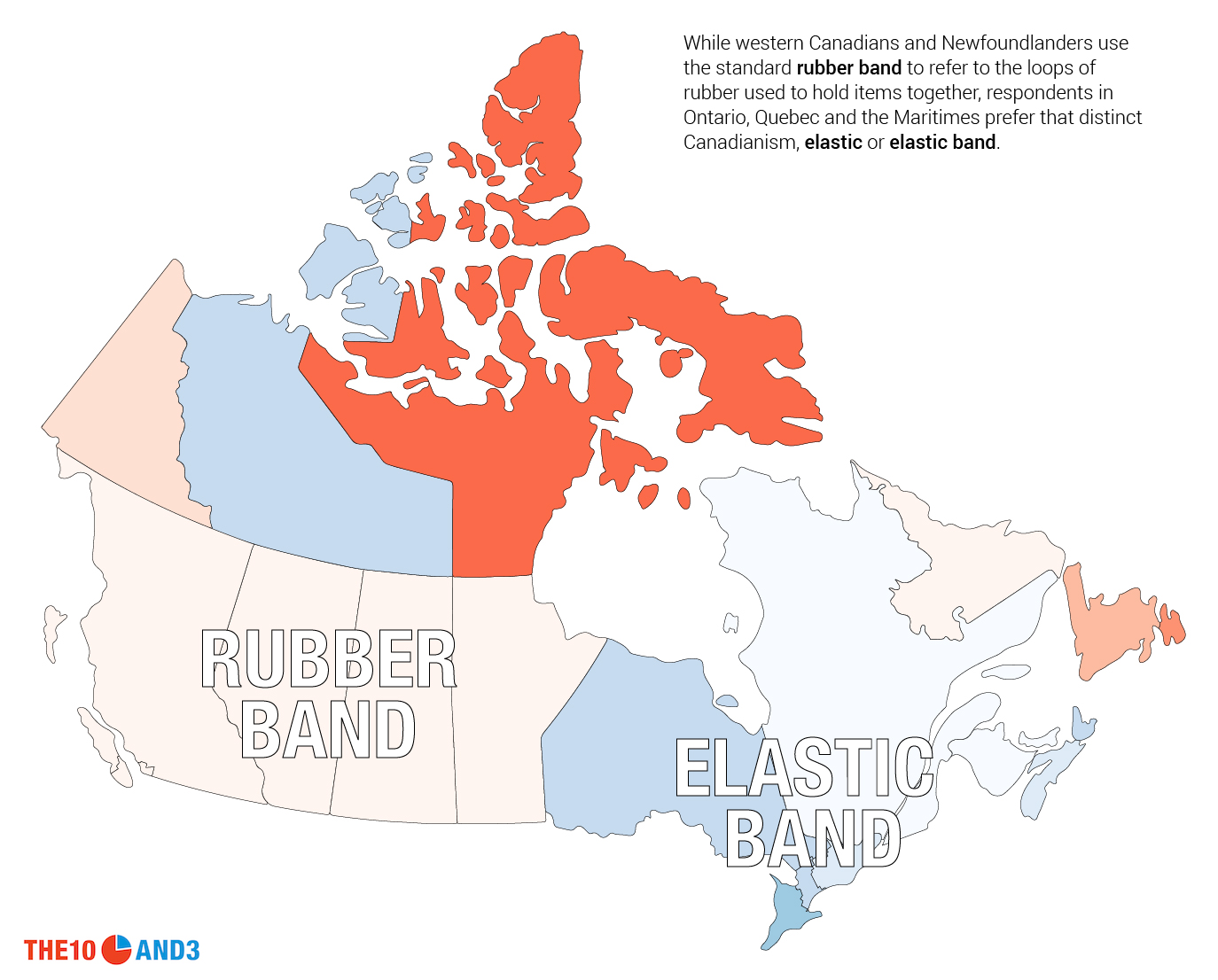

To understand the different ways that Canadians speak, we conducted an online survey of English-speaking Canadians, asking 35 questions about everything from what you call a carbonated, sugary beverage (pop vs soda vs soft drink) to the preferred term for an evening meal (the great supper vs dinner debate). We then mapped the results, revealing some stark and surprising linguistic patterns across the country. In the maps that follow, each colour represents a term or pronunciation being most dominant in that region, and the intensity of the colour corresponds to its level of dominance there. If a region has a white or very light colour, then there is no particularly dominant term in that place.

We collected over 9500 responses from across the country, including from every province and territory, as well as a significant number from interesting linguistic subregions like Cape Breton, Labrador and the Avalon Peninsula in Newfoundland. We also collected a significant number of responses from some of Canada’s most populous provinces, allowing us to study the differences between densely populated urban areas (like the Greater Toronto Area and southwestern BC) and more sparsely populated, rural areas (like Northern Ontario and the BC Interior). The maps show only Canadians who both grew up and currently reside in the same province or territory, which helps to isolate regional influences in language.

Canadianisms

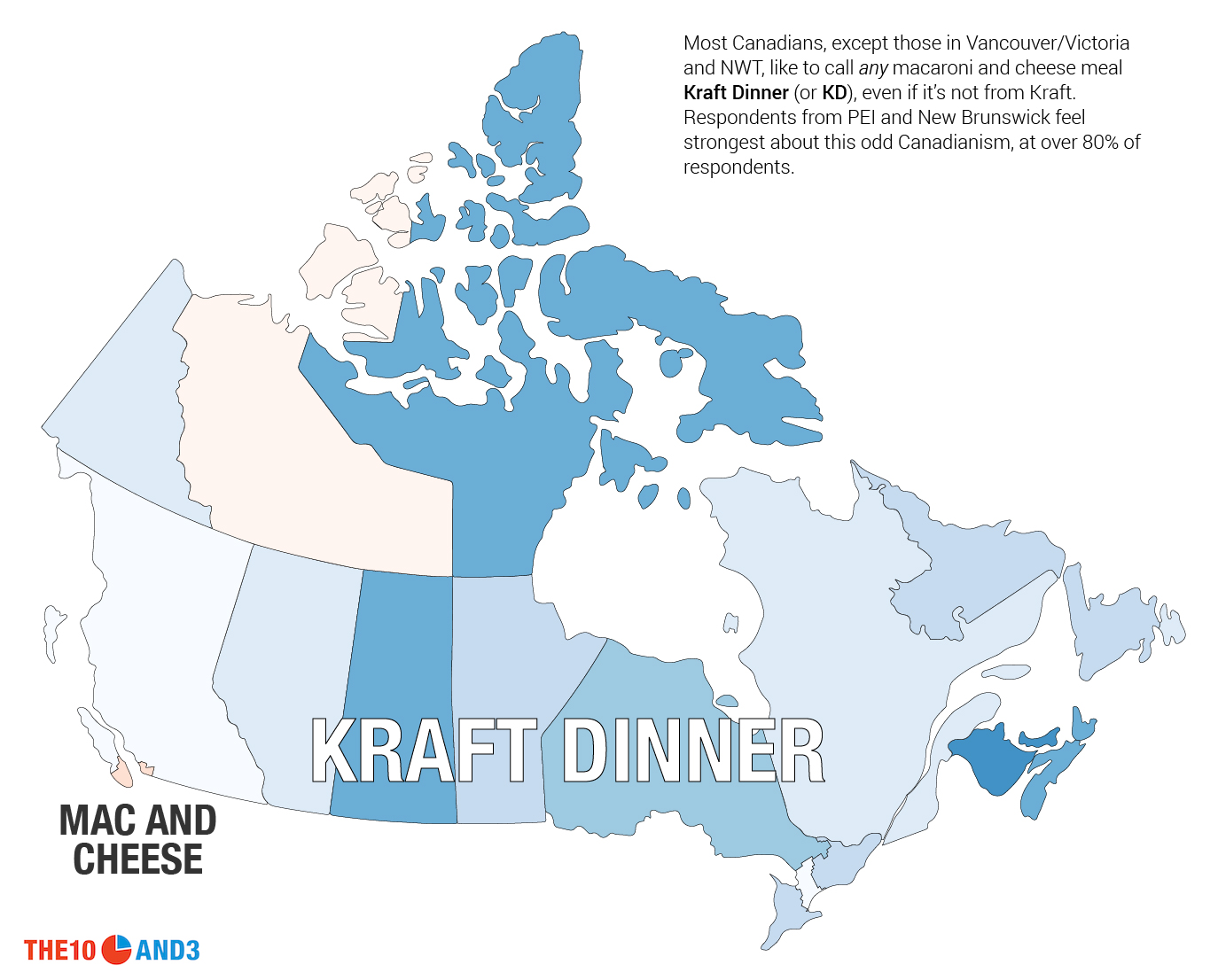

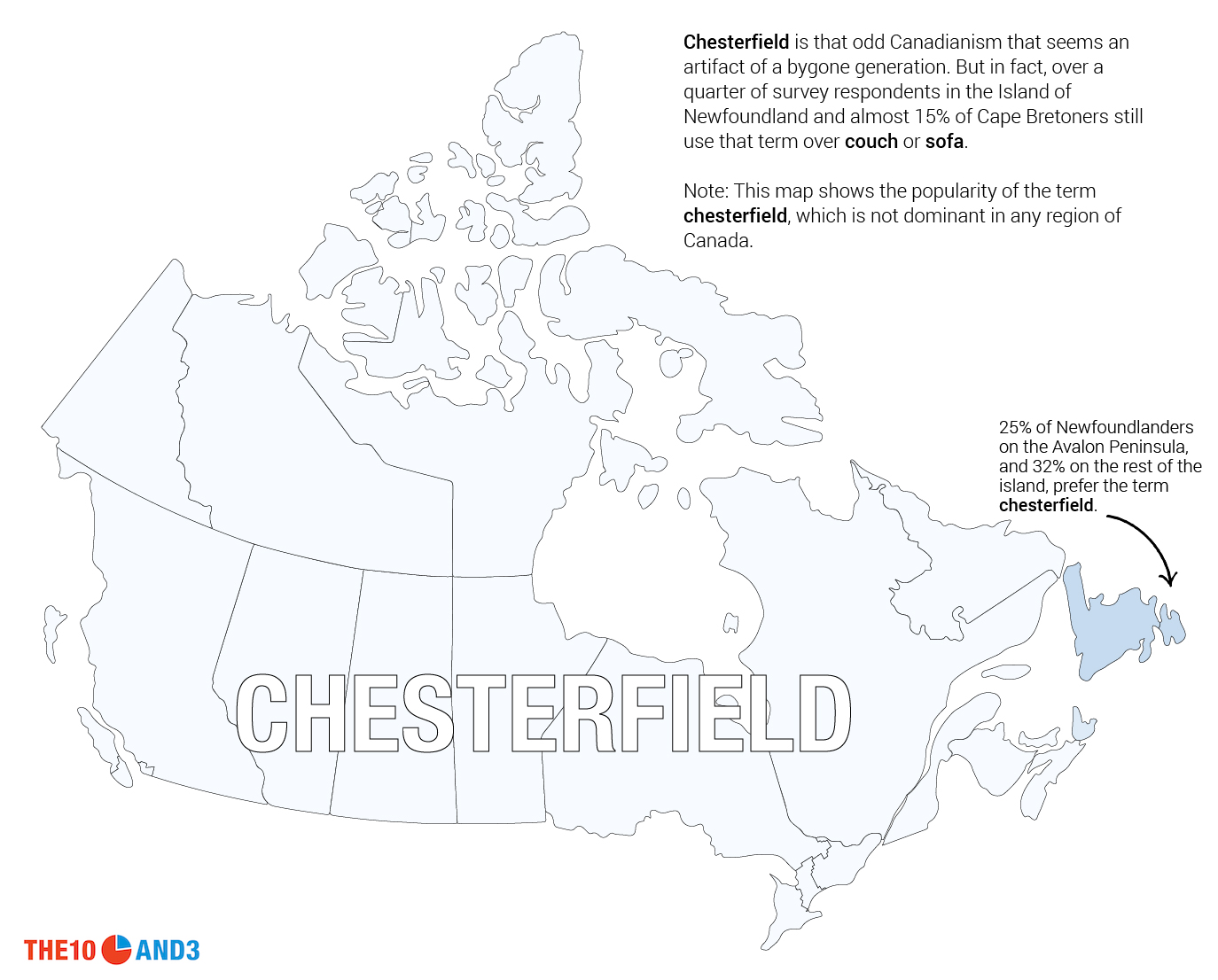

Canada is known for some of its unique vocabulary, like chesterfield, toque, Kraft Dinner and even garburator. But how prevalent are these terms in reality, and what regions of the country embrace them most fully?

Strong regionalisms

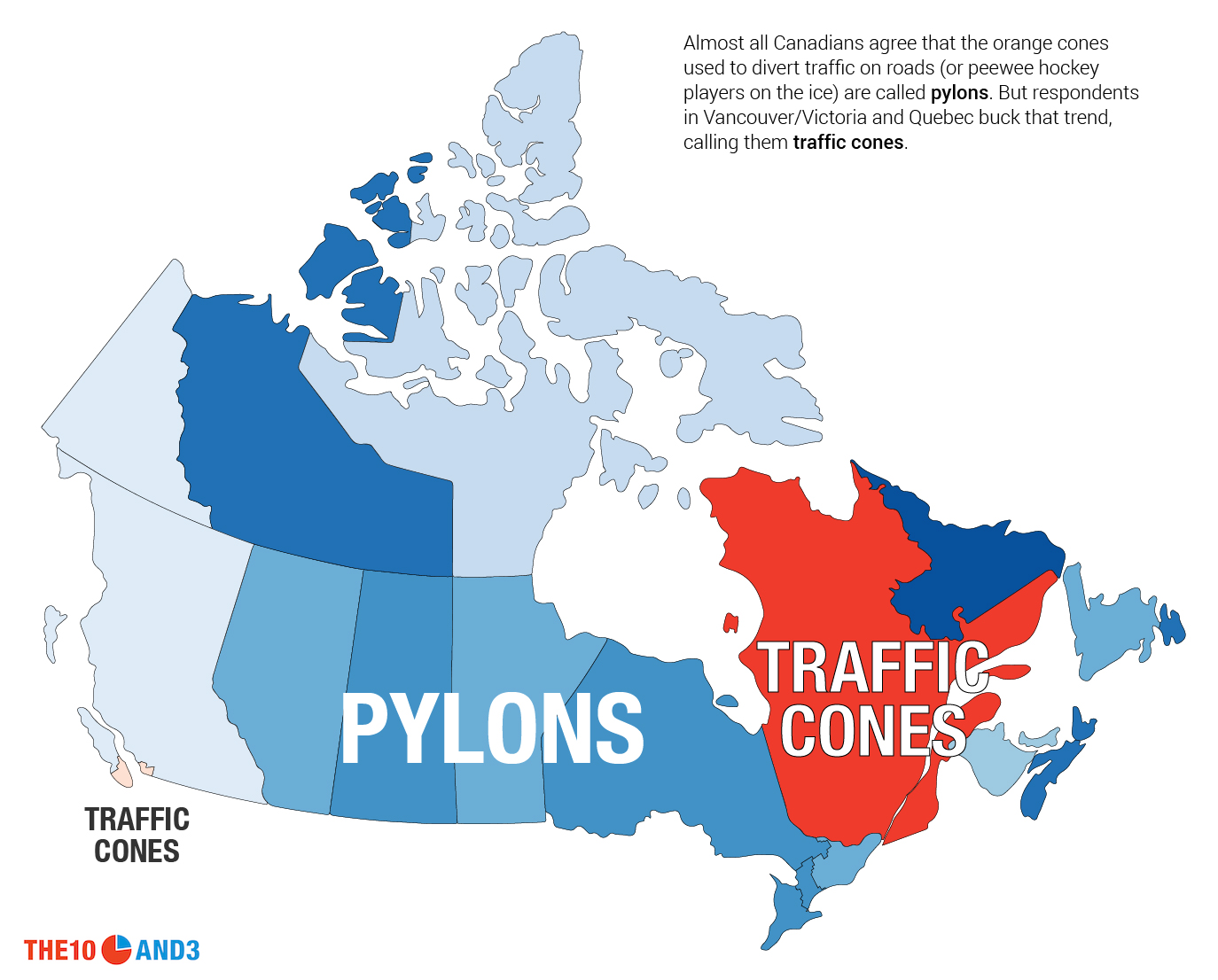

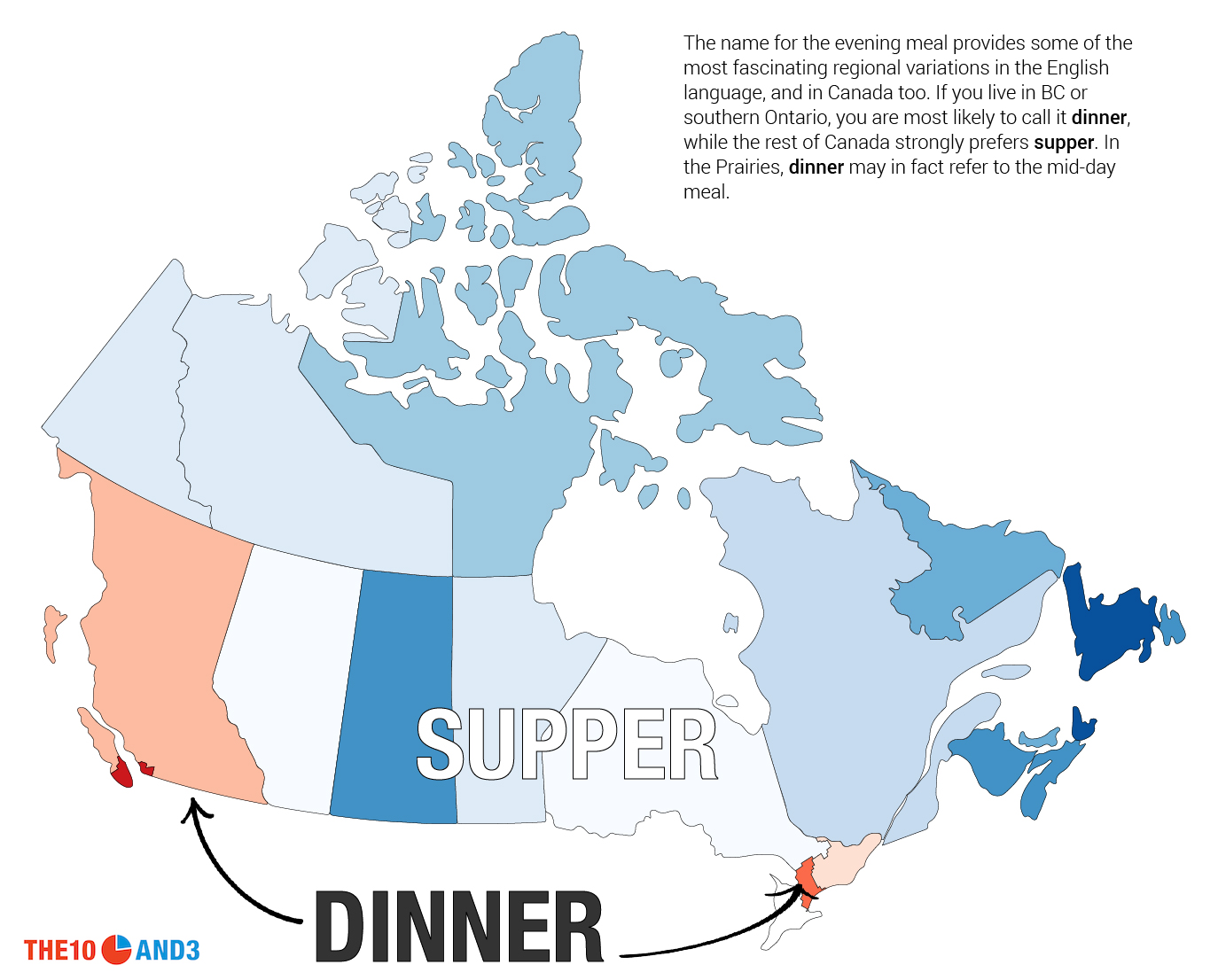

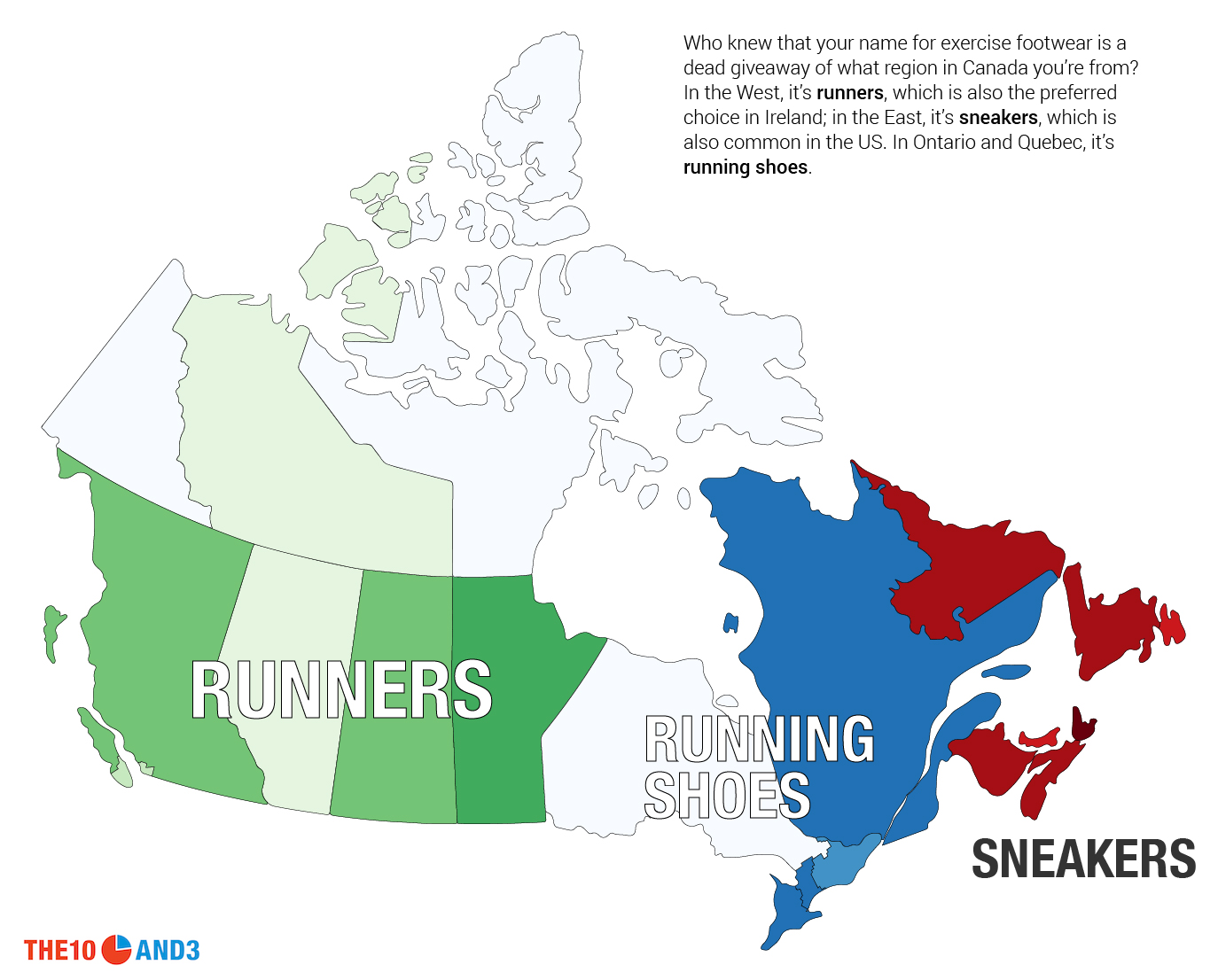

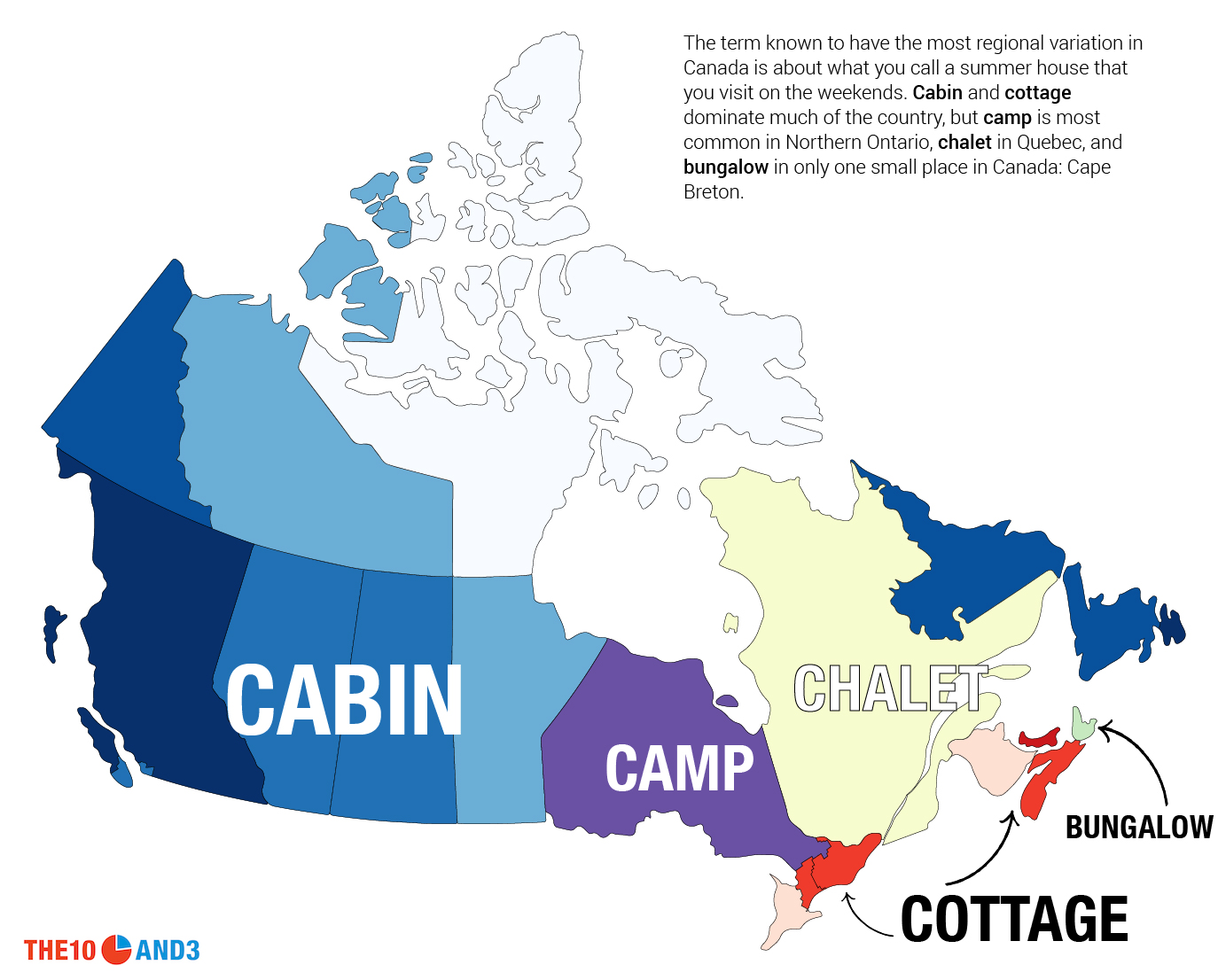

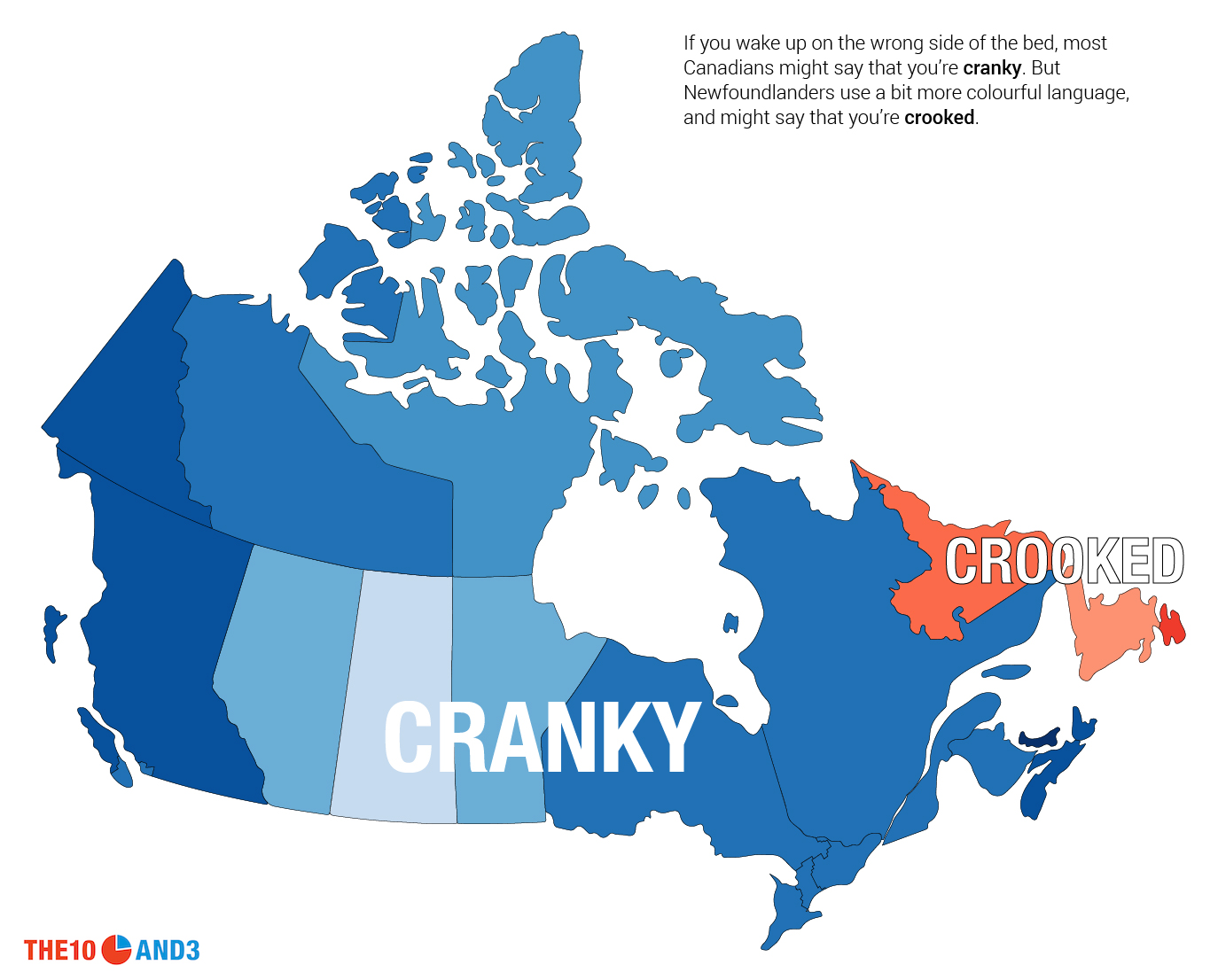

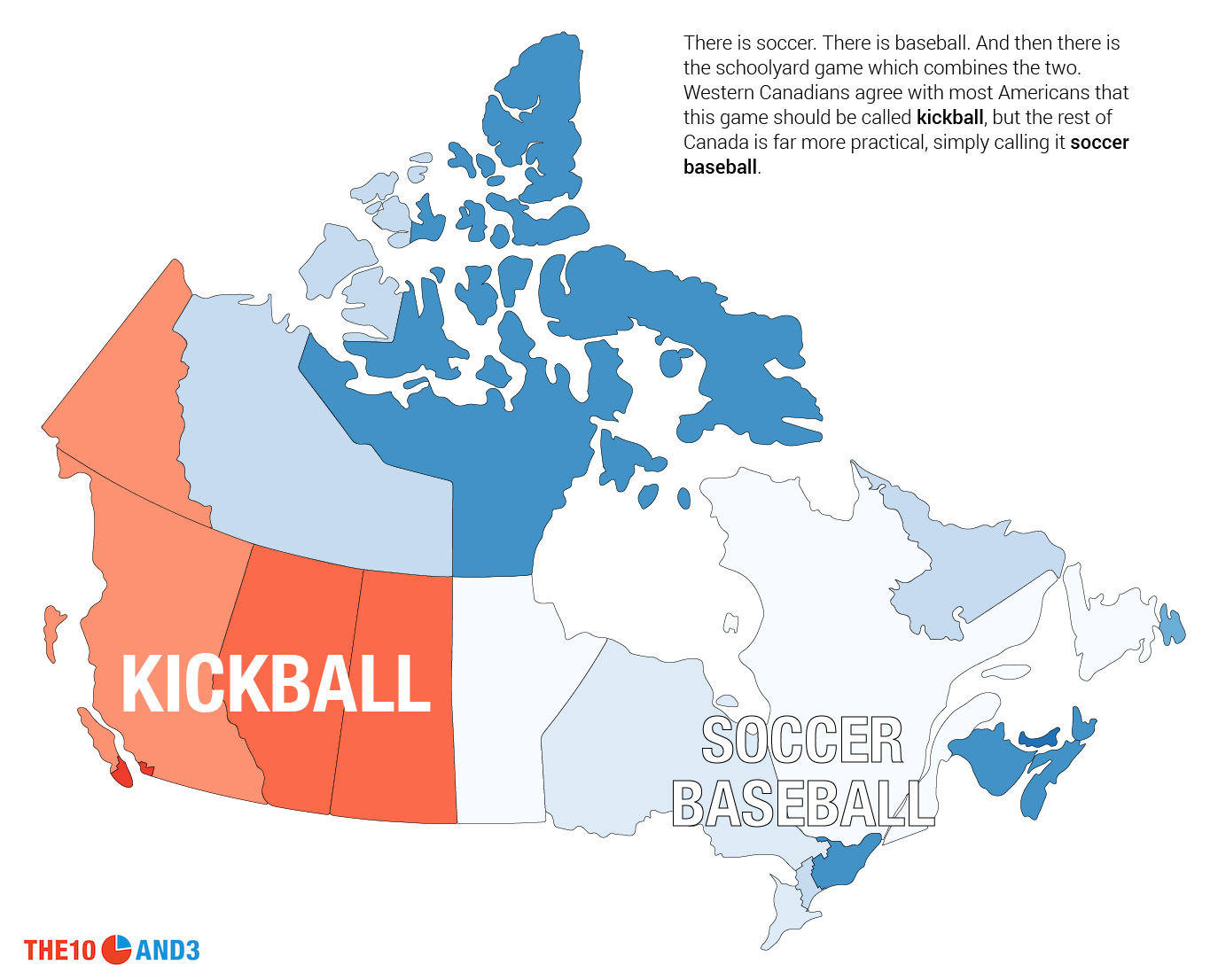

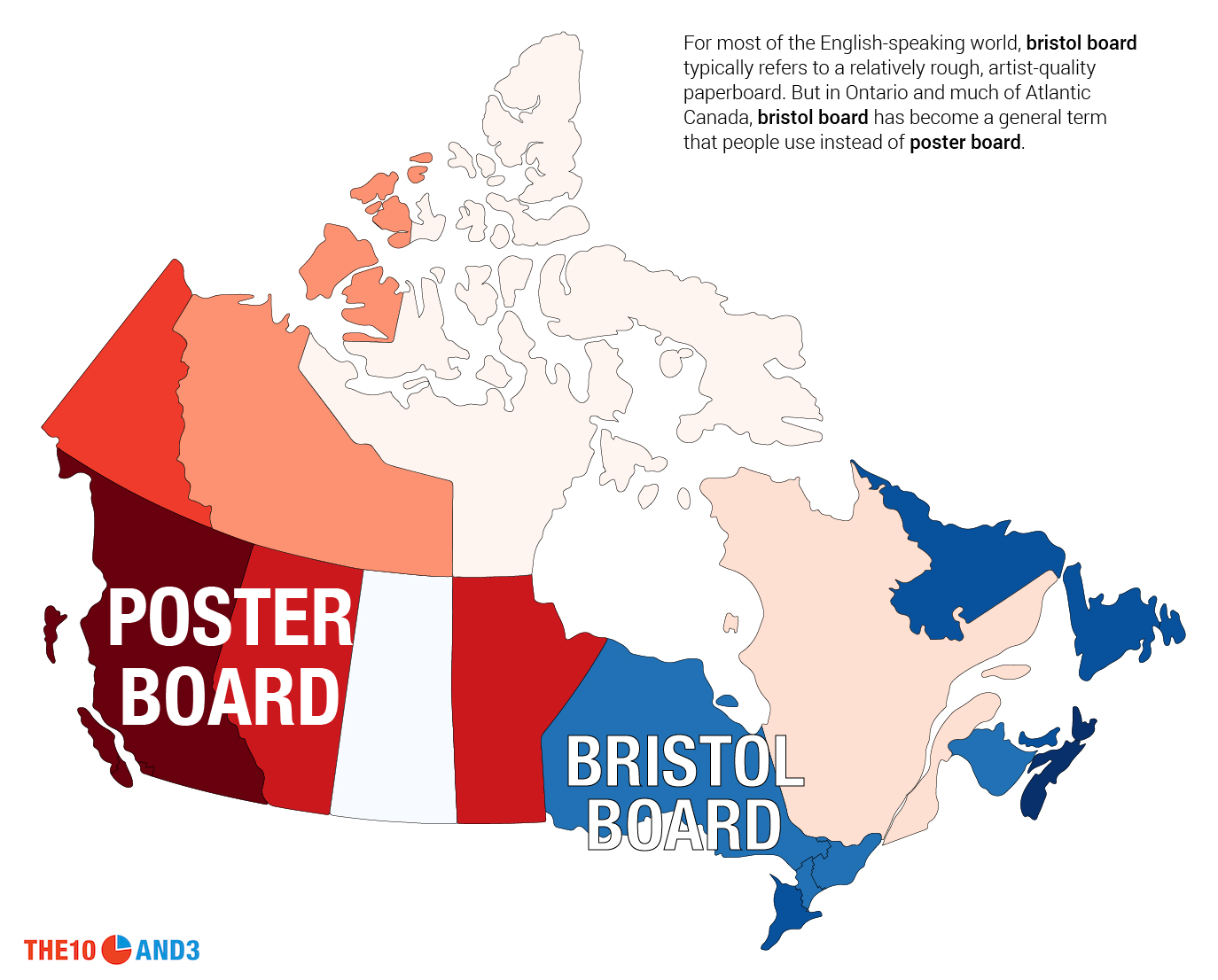

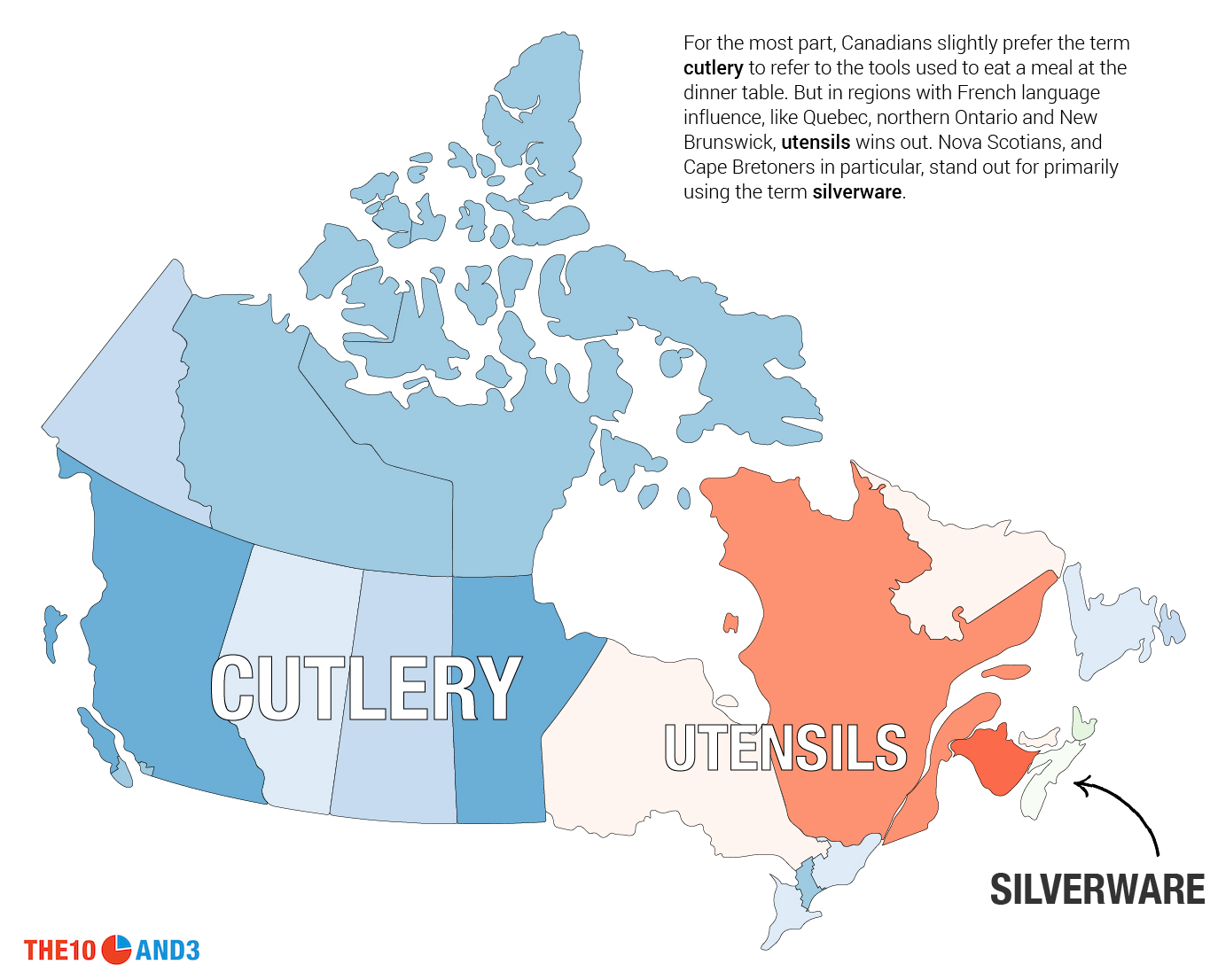

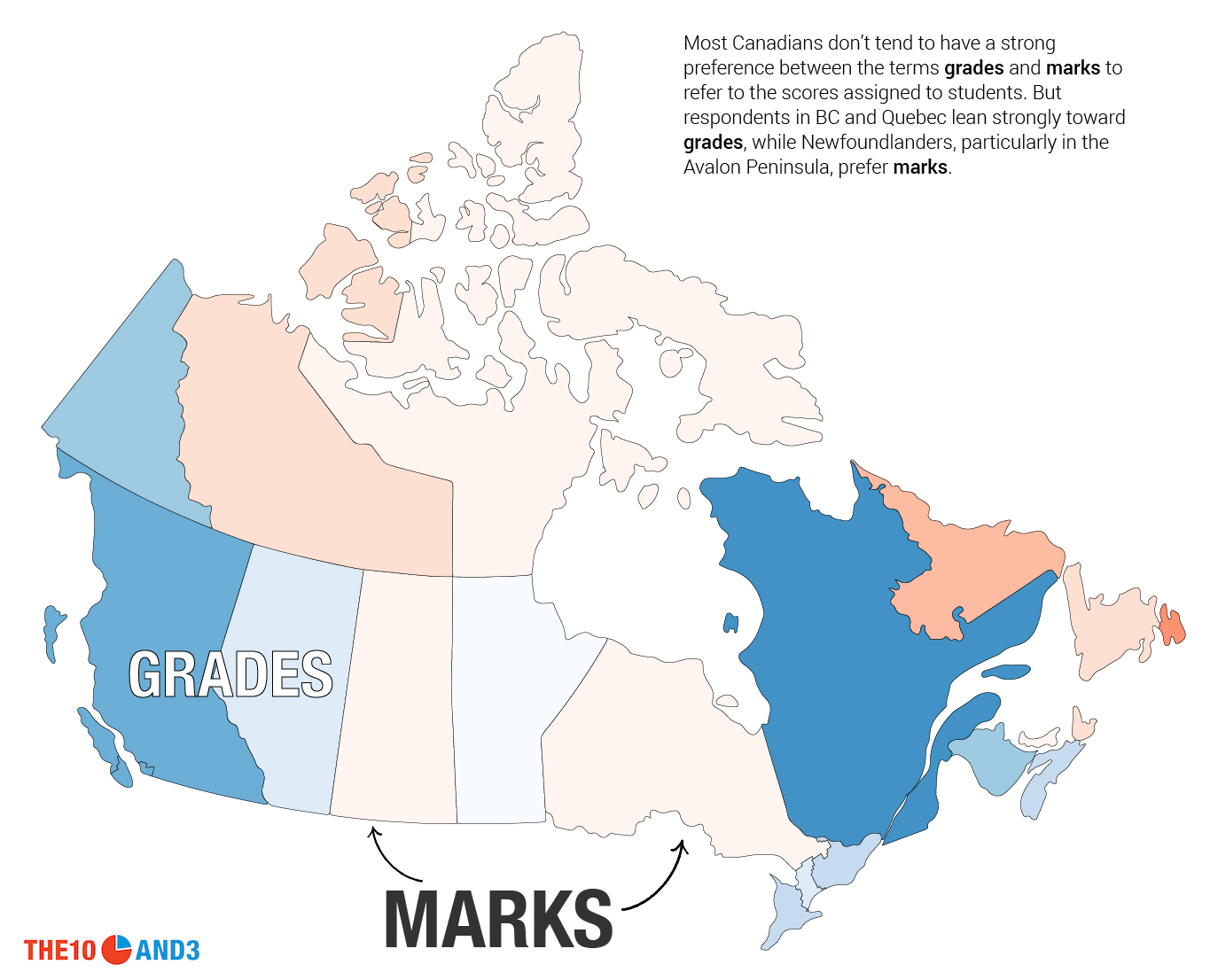

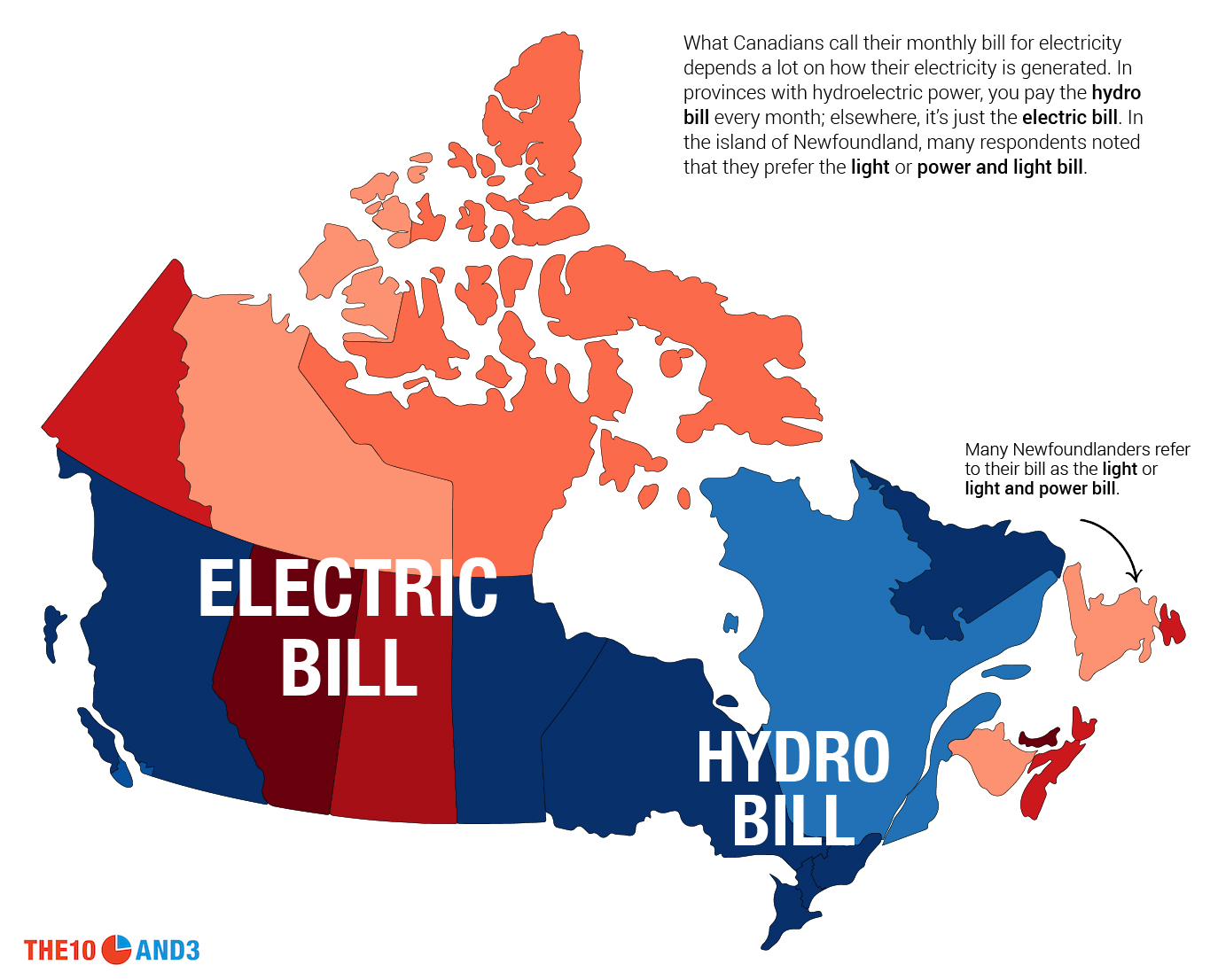

It can be easy to forget how diverse Canada is in terms of culture, politics, and of course, language. In these survey questions, we learned that there are striking regional differences in the words we use to describe some of the simplest ideas.

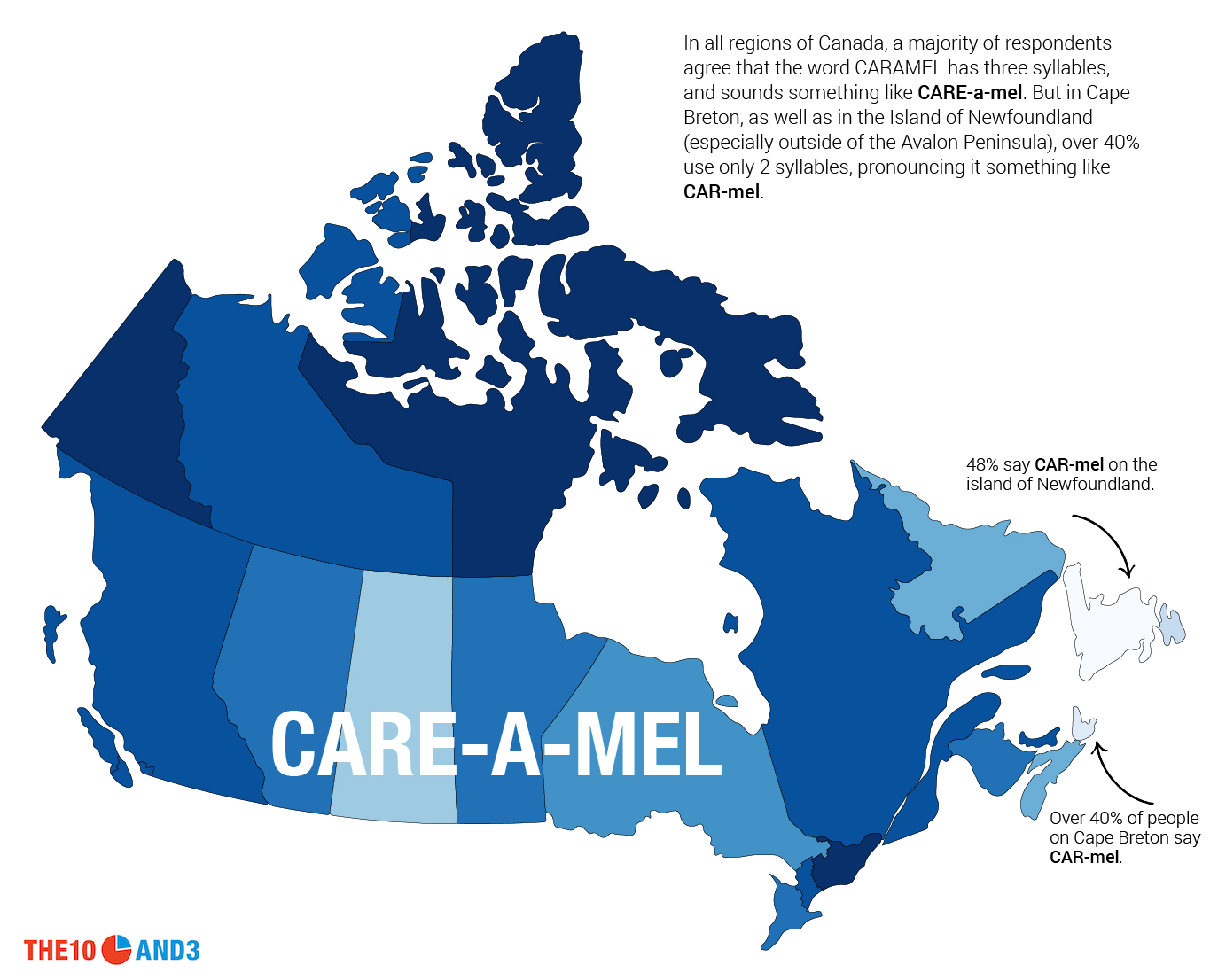

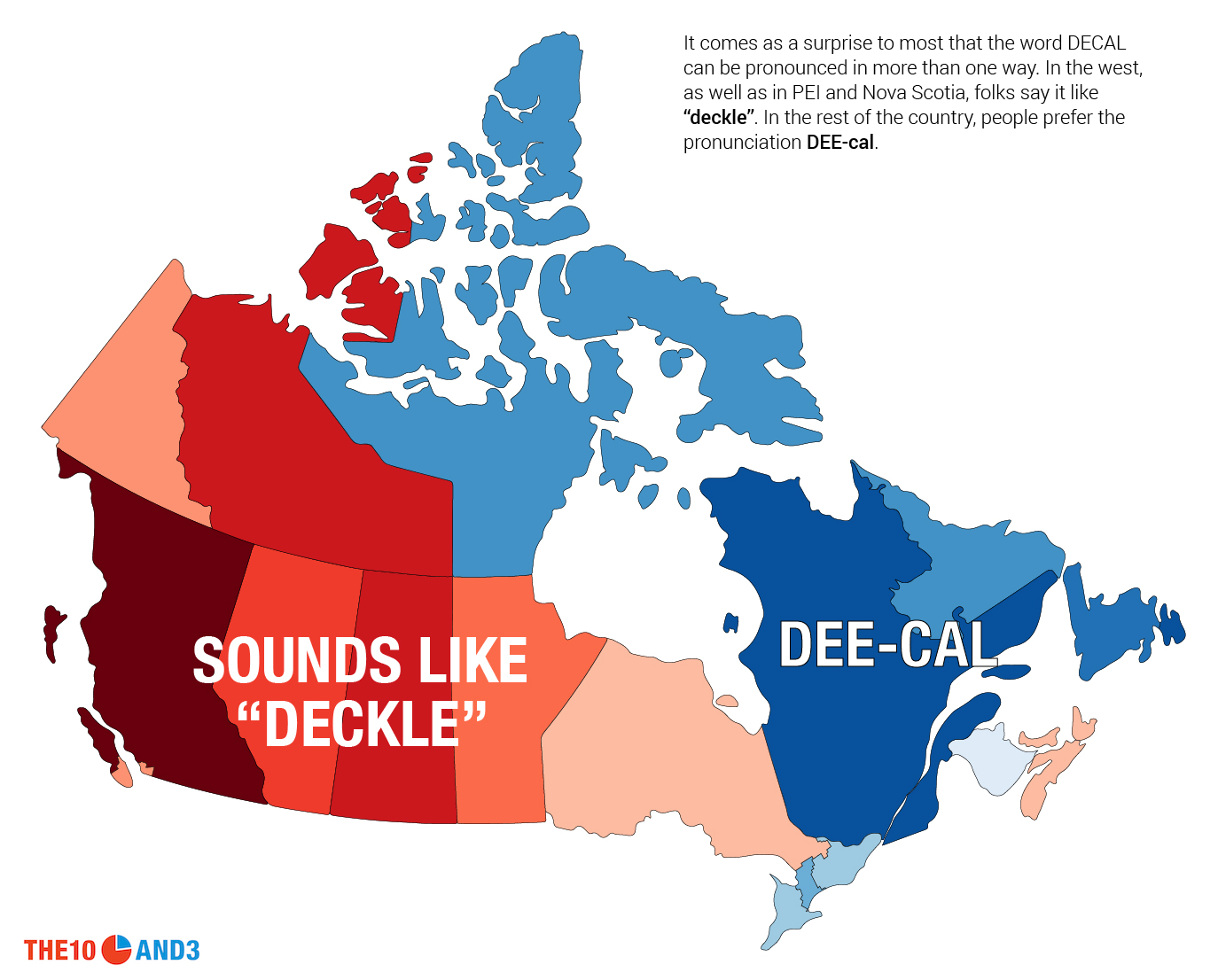

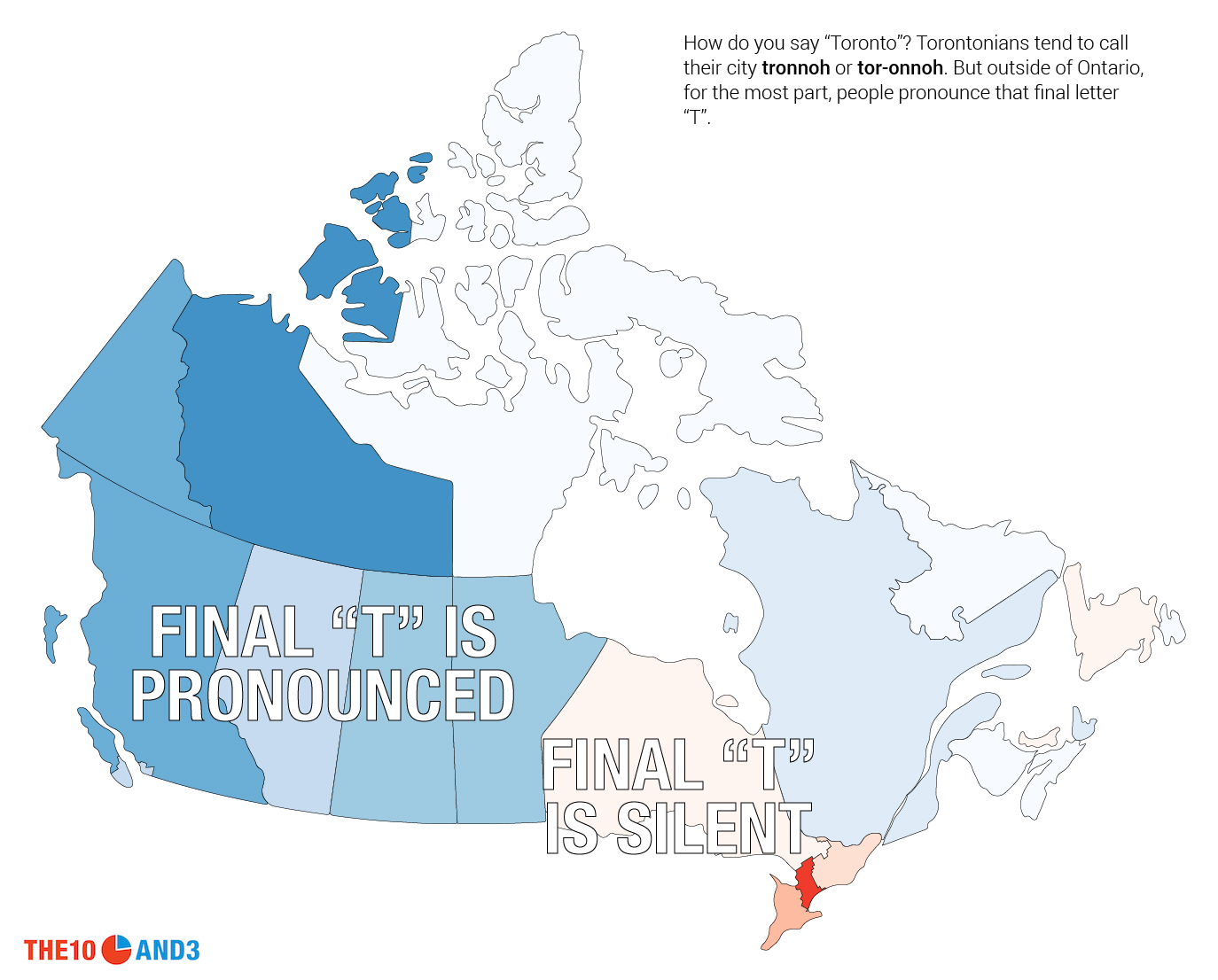

How we pronounce

The Canadian accent is sometimes stereotypically boiled down to a single word: “aboot”. But there is of course so much more to it than that, and an incredible amount of regional diversity. We examined a few such terms in our survey, including the pronunciation of words like caramel, decal and even the city of Toronto.

Some surprising differences

Moving past some of the most obvious differences in the way Canadians speak, we learned that there continue to be some fascinating but subtle regional trend that govern the way we call everything from our monthly utility bill to our dinner table tools.

Methodology and Discussion

We are grateful for Professor Charles Boberg’s help and guidance in reviewing our survey and providing insight and historical context into the patterns that we observed. Our study is of course not the first to examine the different ways that Canadians speak. But it is to our knowledge the largest recent national-level survey of Canadian English, covering Canada’s vast geographical scope and diversity, reaching a significant number of respondents from every province and territory, as well as important linguistic subregions in the country.

Our online survey was conducted primarily via social media over a month in June 2017, gathering over 9500 responses. In our mapping, we restricted only to respondents who both grew up and currently live in the same province. For provinces with subdivided regions like Ontario or Nova Scotia, we mapped according to the region where the respondent grew up. We had at least 25 respondents in every province and subregion, but had many hundreds of responses in almost all areas except the Territories.

While our survey method provided an efficient means of getting many responses, our survey respondents are not representative of all Canadians in the standard statistical sense. Respondents to our survey provided their age and education level, and in aggregate they tended to skew younger and more educated than the overall population. As a result, some questions may display certain kinds of biases; for instance, the term chesterfield is known to be more common among older Canadians, so our data likely underestimates the prevalence of this term as compared to couch or sofa.

Nevertheless, as our analysis primarily focuses on geographic distributions, we are confident that the observed trends are real and meaningful. Indeed, our survey results for some well-studied variables in the linguistics community, like the name of a lakeside summer home (cabin/cottage/camp), the name of the evening meal, and others, closely match previous results. Consequently, Boberg notes that this “… suggest[s] that they represent real patterns and not chance findings influenced by [our] particular method.”

Some questions for our survey were adapted from previously studied language variables in past studies and surveys – including Boberg’s influential North American Regional Vocabulary Survey – while others were drawn from our own research and observations. The most interesting results were presented in this article.

We began with a set of mapping divisions used in the North American Regional Vocabulary Survey; that is, each province is treated as a single linguistic unit, while also subdividing British Columbia into two regions — the southwest urban Vancouver/Victoria region, and the rest — and Ontario into four regions — southwestern Ontario, the Greater Toronto Area, eastern Ontario, and northern Ontario. We then added the three territories, as we had sufficient data for each, as well as several interesting linguistic regions that to our knowledge had not been fully studied in a pan-Canadian survey such as this: Cape Breton in Nova Scotia, Labrador, and the Avalon Peninsula in Newfoundland.