A recent study in the journal Addiction revealed that the average Canadian drinks 50% more alcohol per year than the average world citizen. Surprised? Neither were we. Anyone who has lived through a long, cold Canadian winter knows that Canucks can more than hold their own against international drinking heavyweights like the Russians and Germans. But a look at the provincial data shows that not all Canadians show a similar fervour for beer, wine and spirits. So which regions are bringing up the average, and which consume more moderately?

The Heavy Drinkers

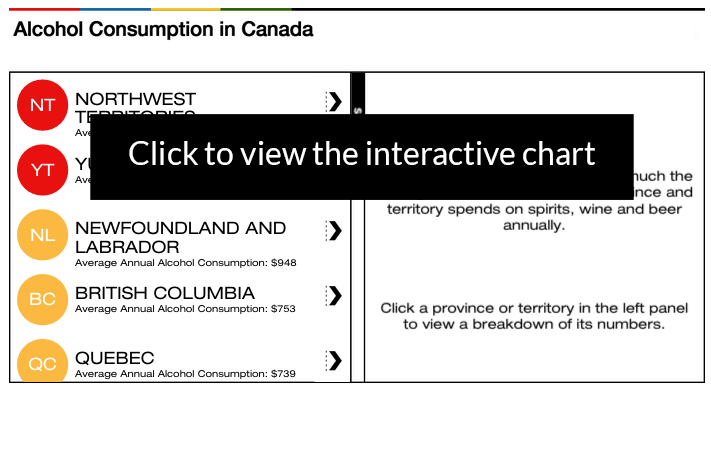

The stereotype goes that when you don’t have much to do for fun, or when your economic opportunities are limited, you drink. The data bears this out. Canadians living in areas with few recreational opportunities often pass their time with a comforting alcoholic beverage. Just on beer alone, residents of Yukon spend a shocking $608 per person each year, while those in the Northwest Territories follow closely at $607. That’s about the cost of a fancy new smartphone, or four new winter tires for your pickup truck, and it’s almost double what the average Canadian spends on beer every year.

But is this disparity simply due to higher prices in the north? Not at all. A two-four of Molson Canadian cans costs $40.55 in the Yukon, roughly the Canadian average (Manitoba tends to have the highest prices for this category of beer). Far down in third place — but certainly not a province to be trifled with — is Newfoundland and Labrador, which clocks in at an average $517 of beer per person. While beer in this province is indeed slightly more expensive on average than in the rest of Canada, it’s clearly volume — not price — that accounts for Newfoundland’s impressive showing.

If you look at spirits, the story is roughly the same. The Northwest Territories leads the pack with an immense annual spend of $548, followed by fellow northerners in the Yukon ($313), and our familiar thirsty easterners Newfoundland and Labrador ($280). Once again, price does not explain the disparity: spirits cost roughly the same across Canada (at least if you are looking at big brands such as Jack Daniel’s whiskey and Smirnoff vodka).

A different narrative emerges when we examine wine. In this category, Quebec is the clear frontrunner. Given their Gallic roots, it hardly comes as a surprise that they would favour a more civilized beverage, with Les Quebecois spending $320 annually per person. But giving Quebec a run for its money is British Columbia ($246), with its emerging reputation as one of Canada’s winemaking powerhouses, particularly in the Okanagan Valley.

Thirsty in the North

The data could not be more clear – the people of the north like to drink. On average, residents of Yukon and the Northwest Territories spend over $1000 per year on beer, spirits and wine, easily outpacing all other provinces and almost doubling the Canadian average. While theories abound for this large disparity, the territories are certainly known for their “frontier alcohol culture”. According to the Northern Review, after alcohol began to arrive in northern Canada in the eighteenth century, a binge drinking style soon became commonplace among many of the native people, historically related to the tradition of feasting during times of plenty. As access to alcohol increased in the 1950s, drinking culture became pervasive and as the data suggest, it has not died down. The sheer isolation (a density of less than 0.1 people per square kilometre) and frigid temperatures (average annual temperatures around freezing in the warmest locations) are likely significant contributing factors to the north’s tradition of finding solace in the drink.

Nunavut is an interesting case. Alcohol is completely banned in much of the territory, and in other areas, is accessible only at a small number of licensed restaurants or via a byzantine and heavily regulated order-by-mail process. This accounts for the low official numbers we observe for Nunavut (just $218 per person annually). On the other hand, Nunavut has a well-documented problem of binge drinking and alcoholism, with much of the alcohol procured unofficially through a network of bootleggers. This may all be shaken up soon, as leaders are currently debating whether to open the territory’s first liquor store.

The (Relative) Teetotalers

Beer is clearly the drink of choice in Canada, outselling both wine and spirits in every province and territory of this country. But at the bottom of the beer-swilling list (excluding Nunavut) is Ontario, whose residents spend just under $300 per person on suds.

On the other hand, some Canadian provinces simply don’t have the palate for wine and spirits. Residents of Saskatchewan thumb their noses at wine culture, consuming just $92 of the beverage each year (likely due in part to the paucity of Saskatchewan wineries). And if you are a spirit-lover in Quebec, you may be a little lonesome. Residents there spend the least each year on the hard stuff.

So besides Nunavut and its unusual circumstances, who takes the national championship for the lowest consumption of alcohol? Prince Edward Island just edges out neighbour New Brunswick for the title. PEI, which held on to its prohibition laws until 1948 — almost 20 years after the rest of the country had given up — appears to still retain something of its puritanical streak. But despite Islanders spending the least overall on booze, alcohol-related struggles still plague the province, with a high rate of binge drinking and surprising rates of fetal alcohol syndrome stressing the province’s health care system.

Methodology

Provincial spending data comes from Statistics Canada’s 2014 figures on the sales of alcoholic beverages per capita for residents 15 and older. In addition to sales of beer, wine and spirits, Statistics Canada reports sales of CCORB (ciders, coolers and other refreshment beverages), which we group together with beer in this article. We collected alcohol prices in each province for a set of popular brands: Molson Canadian 24 cans and bottles, Smirnoff vodka and Jack Daniel’s whiskey.