Gord, Sheila, Graham, Beverley. To many, there is something about these names that is as familiar and quintessentially Canadian as the words chesterfield and poutine.

Is it that these names really are so common in Canada, with our high school yearbooks bursting at the seams with Gords and Sheilas? Or is that they just represent silly stereotypes, made famous by a few celebrities or CBC characters, and have now become lodged in our collective Canadian consciousness?

We dug into the historical birth records to determine, according to the data, what are truly the most distinctively Canadian first names. What we discovered certainly confirms some of these long-standing stereotypes, yet also reveals a surprising glimpse into the waves of immigration that have continually redefined what it means to be Canadian. While names like Lorne, Archibald and Gwendoline were typical of the 1920s and 1930s, by the middle of the century, these British and Germanic monikers gave way to Italian names like Vincenzo, Giuseppina and Antonietta. By the 21st century, given names like Zainab, Armaan and Gurleen, which would have sounded altogether foreign to the Canada of yesteryear, have come to define the new Canadian identity.

What we did

We realized that just because a name is popular in Canada, that doesn’t make it distinctively Canadian. Names like Liam and Noah for boys and Sophia and Olivia for girls are the most popular baby names in this country, but they are just as common in the US. So instead, we called a name distinctly Canadian if it appears at a much higher rate in Canada than it does in our culturally similar neighbour, the United States. We called this ratio of the Canadian name rate to the American rate, the Canadian factor of a name. This means, for instance, that you’re much more likely to bump into a person with a high Canadian factor name while walking the streets of Toronto or Calgary than New York or Dallas.

We looked at birth data stretching back to the 1920s, and focused on the provinces of English Canada because (i) Quebec doesn’t provide comprehensive name data to the public and (ii) it is less compelling and clear that names in Quebec should be compared to those in, say, the United States or even France.

Finally, note that we did choose to include French Canadian names in our results, as long as they are common in provinces outside of Quebec.

The Names

Names marked with an asterisk (*) have multiple common spellings, like Graeme/Graham and Chantal/Chantel/Chantelle.

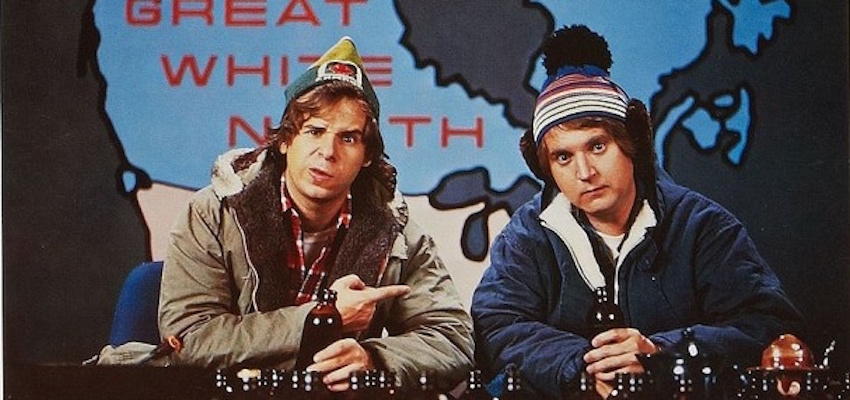

In the early part of the 20th century, being Canadian most likely meant having roots in Great Britain, as a result of the Great Migration to Canada in the early 19th century and further waves of immigration from the British Isles. Consequently, the most Canadian names of the 1920s, 30s and even 40s have a distinctly British flavour, featuring female names like Gwendoline, Georgina, Beverley and Lilian, and male names like Ian, Angus, Colin and Graham.

However, the name Lorne stands out as being particularly Canadian, coming in at over 100 times more common in Canada than in the United States. Famous Canadians like actor Lorne Greene (b. 1915) and Saturday Night Live creator Lorne Michaels (b. 1944) can most likely attribute their naming to the popularity of British nobleman the Marquess of Lorne, who served as Governor General of Canada from 1878 to 1883.

By the 1950s and 1960s, however, the effects of new waves of European immigration were felt in how Canadians were named. Italian immigrants, who were comfortable giving their children names from the motherland while still assimilating culturally to their new country, strongly influenced Canada’s naming trends. Among males, Giuseppe, Paolo and Franco dominate the list, while among females the names Giuseppina, Antonietta and Giovanna became distinctly Canadian-sounding first names.

Giuseppina, specifically, has an intriguing and very Canadian backstory. In 1960, a documentary film by that name was released in Britain, featuring a charming young character called Giuseppina. The film later won an Oscar for best short documentary, and moreover, the BBC soon came to use the movie as a trade test colour film, broadcasting it more than 180 times over the next decade. The film’s success and prominence on BBC (a channel whose programs were frequently rebroadcast on Canadian television) no doubt made Giuseppina a much more popular name in Canada than in the United States.

By the late 20th century, the Canadian factor ratios that we compute rarely rise above 10 or 15, suggesting that naming trends in Canada have more closely converged with the United States, and so very few first names in this generation deserve to be classified as distinctly Canadian. This is particularly true among female names, where the relative popularity of top-ranked Kimberley, Chantal and Gillian fail to approach the wildly distinctive heights of the female names of earlier years. On the other hand, among males, the names Darcy and Graham (also spelled Graeme) became extremely common in Canada relative to our American neighbours. Athletes like hockey player Darcy Tucker (b. 1975) and golfer Graham DeLaet (b. 1982) are examples of this naming trend. At the same time, French names Luc, Stephane and Mathieu, which turned out to be quite common outside of Quebec, also help define a generation of men born in the 1970s and 80s.

While the new millennium in Canada did not produce a bounty of extraordinarily Canadian-sounding names (almost no names have a Canadian factor above 20), there is a distinct introduction of South Asian names which have increasingly begun to define the national identity. Punjabi names like Gurleen, Harleen and Jasleen, which were especially popular in the 2000s in British Columbia, began sounding increasingly Canadian, while other South Asian names like Simran, Zahra and Armaan also started to appear. Middle Eastern names such as Syed, Muhammad and Zainab began to make their way into the list as well.

Perhaps, as we observe with the deluge and then quick retreat of Italian names of the 50s and 60s, children of today’s South Asian immigrants will revert to more “traditional” Canadian names once they have children of their own. And then the next wave of immigrants to Canada will once again redefine what it means to have a Canadian name.

Methodology

We collected Canadian baby name data from the Ontario, British Columbia and Nova Scotia, as well as the United States, stretching back to 1920 through 2013; Alberta data went back to 1980. Other provinces and territories do not publicly provide detailed name data (though several provide less useful top 10 or top 100 lists, which we did not use). The provinces we include represent over 75% of the population of English Canada. In each dataset, the count of every single given name is provided per year as long as it occurred at least five times that year.

For each decade, we computed the Canadian factor of each name by calculating the rate that the name occurs in Canada (or more specifically, those four provinces) divided by the rate that it occurs in the United States. Importantly, we restricted our analysis to names that occur in at least 0.05% of births for that gender in Canada, which allows us to ignore names that are really quite rare but just happen to be more common in Canada than the US. For example, is a name that occurs a handful of times in Canada per year, but never in the US, really a distinctly Canadian name? We think no. Consequently, this restriction ignores any name that occurs fewer than approximately 500 times per decade in Canada.

You might be wondering, how can the name Gordon not be more prominent in the data? In many ways, Gordon is the most quintessential Canadian boys name out there, represented by folk heroes like hockey star Gordie Howe, musicians Gordon Lightfoot and Gord Downie, and actor Gordon Pinsent. We were surprised too, but our answer is simple: the data doesn’t lie. The name was indeed popular in the 1920s and 1930s, just not popular enough, and more importantly, not distinctly popular enough relative to the US, to merit higher rankings. There goes conventional wisdom!

Don’t miss our newest stories! Follow The 10 and 3 on Facebook or Twitter for the latest made-in-Canada maps and visualizations.